Chapter 2: Culture, Community, and Prevention

Introduction

Just as suicide rates vary greatly by country, State, and region, they also vary between and within racial and ethnic groups. While some American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) communities have experienced suicide rates as much as 10 times the national rate, others have rates that are much lower than the national rate. The more extensive research that exists for suicide among Canadian Tribes indicates that some First Nations Tribes have not experienced a single suicide in 15 years. What explains

these variations?

The answer, in large part, is culture. Culture, as described in this chapter, plays a significant role in suicide prevention. Also, as discussed in the next chapter, culture can present some barriers to developing a comprehensive prevention plan.

This chapter explores the relationship between a community, its culture, and prevention. As part of this discussion, it presents factors known to increase a person’s risk of suicide or to protect against it, with special attention given to those factors that place AI/AN youth and young adults at particular risk. The value of cultural connectedness as a protective factor also is examined. However, any attempt to describe suicide and suicidal behavior throughout AI/AN communities cannot fully take into account the vast cultural differences that exist within and between these communities. Caution should be used in any attempt to generalize cultural influences on suicidal behavior across Tribes.

The Concept of Culture

Culture is difficult to define simply. This difficulty may result from the complexity of the many cultures that exist or because each person’s own unique culture defines his or her life and identity in many apparent and unseen ways. David Hoopes and Margaret Pusch, in their writing on multicultural education, made the following attempt to define culture comprehensively:

Culture is the sum total of ways of living, including values, beliefs, aesthetic standards, linguistic expression, patterns of thinking, behavioral norms, and styles of communication which a group of people has developed to assure its survival in a particular physical and human environment. Culture, and the people who are part of it, interact, so that culture is not static. Culture is the response of a group of human beings to the valid and particular needs of its members. It, therefore, has an inherent logic and essential balance between positive and negative dimensions. [Emphasis added.]

In practice, this definition implies that suicide prevention efforts need to acknowledge the cultural context of each individual community. This would include each community’s unique risk and protective factors and how the community understands, discusses, and experiences suicide and suicidal behavior.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) similarly underscored the importance of culture in Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative.

According to the IOM:

Society and culture play an enormous role in guiding how people respond to and view mental health and suicide. Culture influences the way in which mental health and mental illness is understood and defined, the ability of community members to access care, the nature of the care they seek, the quality of the interaction between provider and patient in the health care system, and the response to intervention and treatment.

As these references to culture make clear, suicide does not happen within a vacuum. Rather, suicide reflects the many cultural forces that shape the lives of young people. Because culture, as defined by Hoopes and Pusch, has an “essential balance between positive and negative dimensions,” these forces are both good and bad—in other words, factors that protect against suicide and that increase a young person’s risk.

Research suggests that one of the strongest factors that protect Native youth and young adults against suicidal behavior is their sense of belonging to their culture and community. Similarly, the idea that a loss of culture or community can cause a loss of well-being is well understood by the many AI/ANs whose cultural identity gives purpose and meaning to their life.

Risk and Protective Factors

Before we discuss the protective influences of culture and community, a general discussion of suicide risk and protective factors is in order. Briefly, risk factors are associated with a greater potential for suicide and suicidal behaviors. Protective factors are associated with reducing that potential. It may be helpful to think of these factors in terms of how they may hinder or help a person as he or she travels along life’s path. Protective factors, such as close family bonds, are like roadmaps that help a person stay safely on the correct path. Risk factors, such as substance abuse, are like detours and potholes that can cause a person to stumble off or along the path. Suicide occurs when a person becomes so lost and hopeless that he or she gives up hope of ever

finding the way back or reaching a destination and ends his or her journey forever. It is often the role of Elders and adults, and sometimes the role of older peers, to guide the young along their life’s path and help them avoid, or at least cope with, some of the roadblocks that are bound to appear.

Recognizing the extent to which risk and protective factors exist in a community is the beginning of an effective suicide prevention plan. Ideally, a community will not view the prevention of suicide alone as the sole reason for identifying these factors. As stated at the very beginning of this guide, sound mental health helps young people develop the resilience and skills they need to accept the challenges and gifts that life has to offer. Communities can and should identify factors that will promote the balance of its young people while also reducing or eliminating factors that increase their risk of suicide. Many programs, such as those described in Chapter 7: Promising Suicide Prevention Programs, enable a community to do both effectively.

Risk Factors

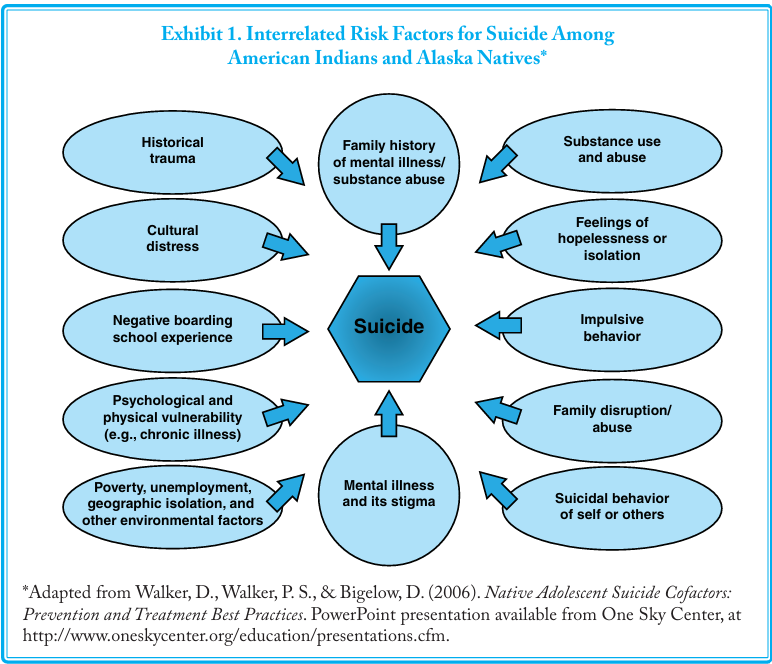

Suicide is complex, and there is no single reason, cause, or emotional state that directly leads to suicide. Substantial research has been conducted on suicidal behavior, risk factors, and trigger events in the general population, but research within AI/AN communities is comparatively limited. Exhibit 1 illustrates what current research into AI/AN suicide suggests are risk factors that place any individual at risk (e.g., mental illness and substance abuse) together with factors that are unique to AI/ANs (e.g., historical trauma).

Risk factors can be divided into those that a community can change and those that it cannot change to reduce a person’s risk of suicide. Some changeable risk factors, such as substance abuse, are like a bear that crosses our path along life’s journey. If we are trained in the ways of bears, we know how to avoid them and the dangers they present. A community working together also can drive the bear away. Other changeable risk factors, such as exposure to bullying and violence, are like a tree that falls across the path. If we have the skills to cope with this challenge and remove it from the path, we can proceed with our journey. A community, for example, could help its children develop the resilience and problem-solving skills that enable them to cope with bullying, violence, or other challenges that may occur during their journey.

Factors that cannot be changed, such as age, gender, and genetics, are different in that neither communities nor individuals can alter the risk of suicide they represent. For example, within AI/AN communities, the group at the highest risk for suicide attempts is females between the ages of 15 and 24. Those at highest risk of completed suicides are males in the same age group. The age and gender of the individuals cannot be changed, even though these characteristics place them in groups at higher risk. This is similar to these youth having to travel down an unavoidable path known to be more dangerous. Unchangeable risk factors for suicide, however, do not predict anything, especially suicidal behavior. No matter how high the rates of suicide within any particular group, most of the individuals within the group do not plan, attempt, or complete suicide. In addition, while a community cannot change any of these factors, its members can be aware of the increased risk for suicide that these factors present. Mental health promotion and suicide prevention programs focused on youth and young adults in higher-risk groups can help them navigate their paths safely.

Just as one example, consider how a community might offer programs to help its young males — the group at greatest risk of completed suicides — cope with life’s demands. The reasons why more males than females complete suicide are complex, but one possibility may be the social pressures and family demands placed on males at an early age. Males may feel burdened by the expectations that they will be strong protectors and providers, particularly during a time of high unemployment. In addition, the

traditional role of males of any ethnic group is associated with greater risk-taking behaviors. Currently, these behaviors include substance abuse, aggression, violence, and others that might be considered antisocial.

Young males also appear more reluctant than young females to seek help for a variety of health-related issues, including depression and stressful life events. Whether this lack of help-seeking behavior is the result of stigma, shame, conditioning, attitudes, or not wishing to appear weak, the outcome is the same — young males do not receive needed assistance. However,

while males might not seek help, they may be willing to accept help when offered. If so, then programs that offer support and guidance, such as mentoring, can guide young males safely to adulthood and beyond.

Risk factors have a cumulative effect. That is, the larger the number of risk factors a person is exposed to, the greater the risk of suicide. Risk factors also are interrelated. This relationship appears to be very strong between mental illnesses and substance abuse and between these two factors and suicide. According to the IOM, an estimated 90 percent of individuals who die by suicide have a mental illness, a substance abuse disorder, or both. The next few paragraphs explore this relationship in more detail.

Depression among youth in the general population is significant. Major Depressive Episodes Among Youths Aged 12 to 17 in the United States of America: 2006 — a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) study released in 2008 — concluded that 8.5 percent of adolescents, or the equivalent of 1 in every 12, had experienced a major depressive episode during the past year. This same report also revealed the often devastating effect these major depressive episodes can have on adolescents. Nearly half of adolescents experiencing major depression reported that it severely impaired their ability to function in at least one of four major areas of their everyday lives. These areas are home life, school/work, family relationships, and social life.

In the general population, substance abuse disorders also are common among those who experience serious mental illnesses, which include chronic depression. Among individuals being treated in a mental health setting, 20 to 50 percent also have a substance abuse disorder. The converse also is true: substance abuse is linked to risk factors for mental health problems. Underage drinking, for example, contributes to academic failure, violence, and risky sexual behavior. Among individuals receiving clinical treatment for substance abuse, 50 to 75 percent have a mental illness.

On the positive side, the interrelationship of risk factors means that efforts to reduce one also can help to reduce others. Prevention of suicide thus becomes prevention of mental and substance abuse disorders and vice versa. The results of the U.S. Air Force suicide prevention program illustrate this connection. In 1996, in addition to specific training in suicide prevention, the U.S. Air Force introduced a broad-based program within its community to increase its general understanding of mental health and

decrease the stigma of seeking help for a mental or behavioral problem. The outcome of the program was that while suicides were reduced by 33 percent, homicides also were reduced by 52 percent. Serious domestic violence rates dropped by 54 percent. Clearly, actions taken to reduce self-harm also help to reduce other forms of personal violence that threaten a community’s mental health.

Factors Placing AI/AN Youth at Increased Risk

Certain risk factors are more common among AI/AN youth and may contribute significantly to their higher suicide rate. These factors are not part of the AI/AN culture but, instead, may be symptoms of other factors such as poverty and depression that affect AI/AN communities disproportionately.

AI/AN youth aged 12 to 17 have the highest rate of alcohol use of all racial/ethnic groups. In 2006, more than 20 percent, or one out of every five AI/AN youth, engaged in underage drinking. During the same time period, 15 percent of AI/AN youth aged 12 to 17 had used marijuana within the past month. This rate is more than double that of any other racial group. AI/AN youth also were more likely than other groups to “perceive minimal risk of harm from substance use.” Research indicates that the lower the perceived risk, the less likely a person is to seek help for substance abuse. Other risk factors specific to AI/AN youth are the perceived discrimination felt by AI/AN adolescents, the racism they experience, and the related stress associated with these issues.

Historical Trauma as a Risk Factor

In the definition of culture given earlier, Hoopes and Pusch state that culture is what a group of people have developed “to assure its survival in a particular physical and human environment.” This statement raises serious questions about the way in which historical trauma may contribute to the suicide rates of AI/ANs. What happens to a group of people when they are torn away

from their culture? What happens to their ability to survive? How do they adapt to trauma and what effect does this adaptation have on them personally and as part of a community? Because “culture, and the people who are part of it, interact,” these reactions to trauma become part of the culture.

Historical trauma is a risk factor for suicide that affects multiple generations of AI/ANs. Historical trauma includes forced relocation,

the removal of children who were sent to boarding schools, the prohibition of the practice of language and cultural traditions, and the outlawing of traditional religious practices. These past attempts to eliminate the AI/AN culture are well-documented, and the lasting influence of this legacy of victimization cannot be underestimated.

Many parents and grandparents of young adults who currently are at risk of suicide may have experienced these traumas directly. They may have been removed from their parents and forced into boarding schools or been raised by parents who grew up in boarding schools. As described in The History of Victimization in Native Communities, “It is important to realize the historical content of victimization is not limited to individuals since all Native families have a collective history of trauma and abuse.”

Elders who lived though the boarding school experience are “[N]ative children [who] suffered deprivations beyond description and those who did survive became the wounded guardians of the culture and tentative parents to the next generation of children." As a result, many parents struggle every day to pass on to the next generation what they themselves may never have received in terms of nurturing or a sense of belonging.

Historical trauma also may have an effect on the help-seeking behavior of AI/ANs, as does AI/AN culture in general. When seeking mental health care, some AI/ANs avoid professional services. They may believe these services represent the “white man’s” system and culture or that the professionals will not understand Native ways. They may have a lack of faith in mental health care in general. Some AI/ANs go to both specialized professional health services and to traditional healing rituals and services. However, not only do a majority of AI/ANs use traditional healing, they rate their healer’s advice 61.4 percent higher than their physician’s advice. In addition, they may not tell the physician everything. Only 14.8 percent of AI/AN patients who see healers tell their physician about their substance use.

Dolores Subia BigFoot, Ph.D., with the Indian Country Child Trauma Center at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, divides trauma into four interrelated categories:

- Cultural trauma is an attack on the fabric of a society, affecting the essence of the community and its members

- Historical trauma is the cumulative exposure of traumatic events that affects an individual and continues to affect subsequent generations.

- Intergenerational trauma occurs when trauma is not resolved, subsequently internalized, and passed from one generation to the next.

- Present trauma is what vulnerable youth are experiencing on a daily basis.

The lesson to be learned about trauma of any form is that it never affects just one person, one family, one generation, or even one community. Like the rock thrown into the pond, the effects of trauma ripple out until its waves touch all shores.

Given the widespread and continuing impact of trauma, a community should ensure that its suicide prevention plan is “trauma-informed.” A trauma-informed plan will be one in which all of its components have been considered and evaluated “in the light of a basic understanding of the role that violence plays in the lives of people seeking mental health and addictions services.” While these words were written to describe direct service system planning, the same approach should apply to suicide prevention planning.

Other Cultural Considerations in Assessing Risk Factors

Many risk factors for suicidal behavior are best understood and addressed within the context of culture and community. These risk factors explore the core questions that challenge youth and young adults, such as “Who am I?”, “What is the meaning of my life?”, and “Where am I going in life?” These factors also explore the broader question faced by all AI/ANs of “Who are we as a people?”

Each of the factors listed below are followed by questions intended to stimulate discussion as to how they apply to youth and young adults within an individual community.

- Feeling disconnected from family and community. The need to belong to a valued group is powerful and deeply

ingrained in all cultures. When this need is blocked or the individual feels disconnected, his or her physical and emotional health can be undermined.

Given that suicide rates are highest among AI/AN adolescent males, how might community leaders and Elders help this

vulnerable group feel connected? How might a community involve adolescents, especially males, in important decisions about their place within the community and their future? How can they have a meaningful role in community prevention efforts?

This factor may have particular significance for young AI/AN men and women returning from military service, some of whom feel isolated by their combat experiences. The New Mexico Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System in Albuquerque, NM, has created a Talking Circle Group for local American Indian veterans. The traditional Talking Circle brings people together in a quiet, respectful manner for the purposes of teaching, listening, learning, and sharing.

The way in which this group is organized and the beliefs behind its slogan—Trauma for American Indian Veterans: The Warrior and the Soul Wound—is intended to help group members feel apart of a larger community and to bring some degree of healing to the mind, heart, body, and spirit. AI/AN communities should engage their military veterans, who may be at higher risk of suicide, in any suicide prevention planning so that their needs can be considered. - Feeling that one is a burden. A feeling that one is of little use to his or her community or a burden to others contributes strongly to the desire for suicide. What are some ways to help youth and young adults feel that they are an important part of the community, that they matter, and that they have a great deal to offer to everyone? How can their contributions be honored? These questions seem to be grounded in strong traditional beliefs, such as the need to honor one’s Elders and to consider how individual actions can affect generations to come. Perhaps the young person who feels the least valuable to a community is the same one that needs to be invited into exploring the solution.

- Unwillingness to seek help because of stigma attached to mental and substance abuse disorders and/or suicidal

thoughts. Stigma is not unique to AI/AN communities, but the cultural values and traditions of a community affect the way in which its young people perceive the risk of harm associated with certain behaviors and the likelihood that they will seek help for them. How does a community talk about mental illness, substance abuse, and suicide? What messages are the youth receiving? How is asking for help viewed within the community? How can a community let them know that asking for help is the brave thing to do? - Suicide contagion or cluster suicide. One or more suicides within a community can trigger additional suicides and suicide attempts, particularly among the family members and close friends of those who first took their lives. In what ways is a community prepared to respond to suicide? What grief-sharing or counseling opportunities are available? Chapter 4: Responding to Suicide discusses suicide response plans in greater detail.

Protective Factors

The reduction of risk factors is essential to any suicide prevention plan. However, a 1999 study of risk and strengthening protective factors among AI/AN youth showed that “adding protective factors was equally or more effective than decreasing risk factors in terms of reducing suicidal risk.” Thus, it may be more valuable for a community to expend limited resources on strengthening protective factors. Protective factors, similar to risk factors, are cumulative and interrelated. Enhancing the way in which young people feel connected to community and family and strengthening their ability to cope with life’s challenges will help them achieve their full potential as individuals as well as avoid suicidal behavior.

Common protective factors that have been found to prevent suicide include:

- Effective and appropriate clinical care for mental, physical, and substance abuse disorders;

- Easy access to a variety of clinical interventions and support for seeking help;

- Restricted access to highly lethal methods of suicide;

- Family and community support;

- Support from ongoing medical and mental health care relationships;

- Learned skills in problem-solving, conflict resolution, and nonviolent handling of disputes; and

- Cultural and religious beliefs that discourage suicide and support self preservation instincts.

Culture as a Protective Factor

Nurturing of children is one of the most basic aspects of AI/AN cultures. Protection of children against harm is embedded in centuries-old spiritual beliefs, child-rearing methods, extended family roles, and systems of clans, bands, or societies. Although this cultural aspect has been threatened and undermined over time as a result of historical trauma, boarding schools, externally imposed social services, alcoholism, and poverty, traditional family values have survived. It is these very traditional family values that will lend strength to Native-led efforts to prevent suicide among their youth and young adults.

According to a document jointly published by the Suicide Prevention Action Network USA and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Suicide Prevention Resource Center, the most significant protective factors against suicide attempts among AI/AN youth are the opportunity to discuss problems with family or friends, feeling connected to their family, and positive emotional health. When these factors are translated into action, culturally sensitive programs that strengthen family ties can help protect Native American adolescents against suicide.

Various studies of the Native cultures suggest additional culturally based protective factors. One study of AIs living on reservations found that individuals with a strong Tribal spiritual orientation were half as likely to report a suicide attempt in their lifetimes. This is consistent with the role of religion as a protective factor in the general population. When a suicide has occurred, the possibility of suicide contagion (i.e., one suicide seeming to cause others) seems to be decreased by a healing process that involves the role of Elders and youth in decision-making, the presence of adult role models, and the use of traditional healing practices.

Cultural Continuity as a Protective Factor

Michael Chandler and Christopher Lalonde, researchers at the University of British Columbia, have found a distinct, positive relationship between some particular aspects of what they refer to as “cultural continuity” and reduced suicide and suicidal behavior among Native youth. Based on their studies, “First Nations communities that succeed in taking steps to preserve their heritage culture and work to control their own destinies are dramatically more successful in insulating their youth against the

risks of suicide.” Their theory is that, when youth have a secure sense of the past, present, and future of their culture, it is easier for them to develop and maintain a sense of connectedness to their own future (i.e., self-continuity).

Although this research is based on First Nations Tribes and Inuit peoples in Canada and the Northern Territory, it has relevance for AI/AN communities. Furthermore, given common U.S. and Canadian concerns about the rising suicide rates within Native communities, cross-border research-sharing can help create solid culturally based prevention models.

Cultural continuity is the extent to which the language, traditions, values, and practices of a culture have continued over time and are likely to continue into the future. In their study, the Canadian researchers found that cultural continuity could be promoted by a Tribe or Village’s control over such things as its educational services, police and fire protection services, and health delivery services by local institutions. Other results of their research demonstrate that indigenous language use, as a marker of cultural persistence, is a strong predictor of health and well-being in Canada’s Aboriginal communities. Furthermore, Tribes and Villages that had “established within their communities certain officially recognized ‘cultural facilities’ to help preserve and enrich their cultural lives” had lower youth suicide rates.

These results should not be surprising. Just as with individuals, a community’s sense of having some control over its daily life can be empowering and contribute to the community’s general well-being. Youth who feel included in this community also share in this well-being, with positive results. Feelings of empowerment and hopelessness do not travel down the same path together.

Another key aspect of cultural continuity is spiritual continuity. Western medicine recently has discovered what many AI/AN Elders always have known: Strong spiritual beliefs and practices are protective and promote survival. Furthermore, issues connected to illness and healing are best understood within the wider domain of a religious or spiritual worldview.

This relationship is too seldom addressed in Western-based suicide prevention planning, even though “cultural and religious beliefs that discourage suicide and support self-preservation instincts” are described as a protective factor in the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention. To bridge the spirituality gap, any discussion of cultural considerations in suicide prevention also must include the spiritual.

Acculturation, Assimilation, and Alternation

As Chandler and LaLonde demonstrate in their studies of First Nations youth, cultural continuity appears to be a strong protective factor against suicide. This finding also implies that cultural disruption would be a risk factor. Several studies support this implication with research that concludes that social disruption caused by dramatic and rapid cultural changes may account for the increased suicide rates among indigenous groups in Alaska and Canada. This conclusion, however, does not fully address

the sometimes conflicting outcomes of the long multigenerational acculturation and assimilation processes of many Tribal communities or the urban Indian experience.

Acculturation is the process whereby the attitudes and behaviors of people from one culture are modified as a result of contact with a different culture. Acculturation implies a mutual influence in which elements of two cultures mingle and merge. For AIs and ANs, acculturation has affected their Tribal structure, religious practices, and community identity, among other cultural aspects.

People undergoing acculturation essentially live in the juncture of two cultures. An AI who lives and works in the city, for example, might receive health care from the city-based Indian Health Service (IHS) services but go home to the reservation for a traditional healing ceremony when needed. An AN might practice a Christian religion while his or her parents or grandparents are grounded in traditional spiritualism.

Depending on the degree to which a person is able to balance elements of the two cultures, an individual undergoing acculturation can feel part of two worlds, one world, or none. Furthermore, when a “clash of cultures” results, traditional values may be lost and not replaced by acceptable values from the new culture. Cultural voids created by acculturation can result in alienation,

identity confusion, depression, alcohol abuse, and suicide.

Assimilation occurs when a member of one culture gives up his or her original cultural identity as he or she acquires a new identity in a second culture. Assimilation may be voluntary or it may be involuntary, as occurred in the AI/AN experience with boarding schools. Some studies suggest that less assimilation into the dominant culture increases an individual’s risk of suicide. The speculation is that these less assimilated individuals are less prepared to handle the stress that may be imposed by their new lifestyle. Conversely, other studies suggest that too much assimilation may strip the individual of the protection that culture provides. This situation, for example, especially appears to be the case for immigrant families who bring their cultural protective factors to their new country, only to see those protective factors disappear in subsequent, assimilating generations.

How, then, can these contradictory views of acculturation and assimilation be resolved? It may be that an important protective factor for many AI/AN youth and young adults is to have a solid foot in both worlds and to feel that this dual identity is acceptable to their peers and community. Without this grounding, they may develop feelings of isolation and alienation that cut them off from the protective factors of either world.

Urban Natives, Cultural Connectedness, and Suicide

As mentioned previously, approximately 2.8 million AI/ANs make up the “invisible Tribe” that does not live on reservations and may lack a strong connection to their culture and community. Currently, more than 65 percent of AI/AN youth live in urban areas.

Because there is no formal public health surveillance system for urban Natives, little is known about suicide rates within this population. Some of what is known comes from a 2004 study published in the American Journal of Public Health, which found that when urban Natives were compared to the general population:

• Their death rate due to unintentional injuries was 38 percent higher;

• Their death rate due to chronic liver disease and cirrhosis was 126 percent higher; and

• Their rate of alcohol-related deaths was 178 percent higher.

Unintentional injuries, substance abuse, and suicide are closely related. Consequently, these figures suggest that the suicide rate of urban Natives also may exceed the national rate.

Researchers are beginning to study protective and risk factors associated with suicide among AI/AN youth living in urban areas as well as those living on reservations and in villages. One such study revealed that while a Native who was raised in an urban setting had a lower rate of suicide ideation than a reservation reared youth, the suicide attempt rate was generally the same. This study goes on to state that there are some distinctive differences in psychological risk factors between these two groups. A history of physical abuse, a friend attempting or completing suicide, and family history of suicidality were positively associated with a history of attempted suicide by AI/AN youth raised in an urban setting. By comparison, depression, conduct disorder, cigarette smoking, a family history of substance abuse, and perceived discrimination were correlated with a history of attempted suicide only within the reservation-reared sample.

The hope is that separate studies of these groups will lead to better prevention and intervention programs that account for each group’s strengths and challenges. Mounting evidence suggests that efforts to reestablish or strengthen the connection between urban Natives and their culture and community may have a significant effect on their mental well-being and their overall quality of life and health.

Conclusion

In developing suicide prevention plans, communities will need to assess the presence of risk and protective factors that affect the balance, or overall well-being, of their members. While attention should be given to reducing risk factors, equal and perhaps greater attention should be given to increasing protective factors that promote overall mental health and well-being. This does not imply that communities should ignore risk factors. Examination of these factors can raise community awareness of the problems that people, especially youth, are facing and draw attention to their need for help and supporting programs and services.

As part of this process, AI/AN communities may wish to identify and incorporate aspects of their culture that promote balance among their young people and also reduce their risk of suicide. These aspects include such things as spiritual beliefs, traditional values and healing methods, spiritual and cultural continuity, and ensuring that their young people have a valued role in preserving their heritage. In addition, communities might wish to encourage and support life skills and coping skills that help prepare youth to live successfully in a bicultural world.