Chapter 6: Community Action

Introduction

Although suicide is an individual act, we cannot understand or prevent such acts simply by considering the behavior of the individual. Just as with another living, interdependent community, there can be no true understanding of the behavior of a bee without considering its relationship to the hive. Similarly, there can be no true understanding of suicide and its prevention without considering how individuals fit within their communities.

This chapter looks at the role of a community in prevention, both in theory and in practice. It first describes two general ways that a community can think about prevention: the public health model and the ecological model. Although presented separately, these models are related. The ecological model is simply an interpretation of the public health model that best fits the way Native communities historically have thought about their relationship to their members and their environment.

As described, both the public health and the ecological models reflect the same key principles of prevention. First, prevention goes beyond a focus on the individual to include all members of a community. Second, prevention is proactive, with health promotion as an essential element of prevention. Third, prevention is collaborative. The broader the base of community involvement, the greater the chances that prevention efforts will succeed. And, finally, everyone within a community has a stake in and responsibility for the health of its individual members.

The second half of this chapter describes tools that a community might use to develop a comprehensive suicide prevention plan.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Strategic Prevention Framework (SPF), which is based on the public health model, provides a set of steps that communities can use to assess their need for action, develop strategies and resources for responding to identified needs, and evaluate the effectiveness of their response. The American Indian Community Suicide Prevention Assessment Tool (see Appendix D) also may help communities assess suicide risks and possible responses. This chapter ends with a few suggestions about how communities can increase the effectiveness of their efforts by engaging all stakeholders in prevention.

The Public Health Model

The U.S. Surgeon General’s Call To Action To Prevent Suicide calls for a public health approach to suicide. As suicide is considered a public health problem, with many complex contributing factors, this approach is very appropriate. In addition, the model’s emphasis on promoting mental health as a way to prevent mental illness holds great promise for American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) communities and lends itself to cultural adaptation.

The easiest way to understand the public health approach is to compare the public health model with the traditional medical model. The medical model focuses primarily on reducing illnesses by treating individuals who already have been diagnosed with a specific disorder. The public health model, on the other hand, is concerned with the health of an entire population. It goes beyond the diagnosis and treatment of individuals to include health promotion and disease prevention. It also includes evaluations of the health of the population at large, the effectiveness of available services, access to services, and how well these services reduce

illnesses. Thus, while the medical model is concerned with restoring the health of an individual, the public health model is concerned with establishing and maintaining the health of a community. The most basic premise of the public health model is that caring for the health of the community protects the individual while caring for the health of an individual protects the community, with an overall benefit to society at large. Mandatory childhood immunizations, which have all but wiped out several once common and deadly diseases, are examples of a successful public health approach.

The medical model also emphasizes the physical or biological causes of an illness, such as a virus or a person’s genetic vulnerability to disease. The public health model views health within a larger context. Health also is affected by the physical, psychological, cultural, and social environments in which people live, work, and go to school. This is a very holistic approach to health that considers many of the factors within a community that contribute to or reduce its health risks. When applied to suicide, the medical model considers the history and health conditions that could lead to suicidal behavior in a single individual. The public health model focuses, instead, on identifying and understanding patterns of suicide and suicidal behavior throughout a community.

Similar to the medical model, there is a protocol, or process, to follow in applying the public health model. The public health model is based on an organized set of steps for identifying threats to a community’s overall health and in developing a comprehensive and effective response. Steps in the public health model are listed below:

- Define the problem (i.e., identify a community’s needs, resources, and readiness to address the problem);

- Assess risk and protective factors;

- Develop and test prevention strategies (i.e., which strategies works best for a community, given its culture and other specific circumstances);

- Implement effective prevention strategies; and

- Monitor and evaluate.

A later section on SAMHSA’s SPF will provide more details on how a community can apply these steps to suicide prevention efforts.

According to the public health model, all members of a community should be involved in promoting the mental health of individual members and preventing mental illnesses. This model represents a dramatically different approach to suicide prevention than many communities first consider taking. A common misperception about suicide prevention is that it is the sole or primary responsibility of the formal mental health system, which focuses on treating individuals who are experiencing a mental or substance abuse crisis. The public health model moves the prevention focus from the clinic into the community. This model recognizes that all members of a community share risk and protective factors and also accepts that an entire community can be affected by the problems experienced by any one individual. Consider, for example, a young man with untreated depression. If his condition causes him to drop out of school, miss work, or drink alcohol or use drugs, then his family, friends, school or workplace,

and community also may suffer consequences. Perhaps most important, the public health model encourages a community to pursue the numerous opportunities it has to prevent mental health problems in young people before they begin.

Under the public health model, all organizations within a community would collaborate in suicide prevention efforts that range from mental health promotion to risk reduction. For example, young people who are the victims or the perpetrators of violence are more prone than others to mental health problems. Families, schools, recreation centers, and the child welfare and juvenile justice systems all might work to teach and reinforce anger management skills in adolescents (promotion) and to identify and refer to counseling those young people who may have experienced violence (prevention).

Similarly, under the public health model, all organizations within a community would help provide services and supports to anyone who experienced a mental health problem, including substance abuse. It would not be enough for a young person simply to be referred to counseling for suicidal behavior. Under this model, a community also would ensure that the person had transportation to counseling services and would not be stigmatized at school or in the workplace for seeking help. Family members also might receive guidance in how to support their child through a difficult time.

A very powerful example of such a comprehensive and community-based public health approach to prevention can be found

in the Western Athabaskan Tribal Nation (a pseudonym used to protect the identity of this Tribe) suicide prevention initiative. In the late 1980s, this Tribe’s rate of suicide and suicidal attempts was 15 times the national average. This rate prompted the Tribal council, the community, and the Indian Health Service (IHS) to work together to establish and expand a comprehensive suicide prevention program. As part of this effort, the Tribe realized that it needed to address the community’s underlying issues of alcoholism, domestic violence, child abuse, and unemployment. Prevention programs aimed at the entire community as well as

individuals at various levels of risk were selected. All key constituents—Tribal leadership, health care providers, parents, Elders, and youth—were involved in planning and implementing the overall suicide prevention plan.

According to the evaluation of this program published in the American Journal of Public Health, the Tribe experienced a steady reduction in suicidal gestures and attempts throughout the course of the program. Self-destructive acts, including suicide completions, among all age groups declined from 36 per year for 1988–1989 to 10 per year for 2000–2001. Among youth ages 11 to 18, the number of suicide attempts dropped from 14.5 per year for 1988–1989 to 1.5 per year for 2000–2001.

Public health lessons learned by the community in reducing suicidal behavior follow.

- Suicide prevention programs should not focus on a limited range of self-destructive behaviors; rather, programs must emphasize the root conditions and an array of social, psychological, and developmental issues. Community involvement from the beginning is critical in developing strategies with which to address issues identified in a culturally, environmentally, and clinically appropriate manner.

- Flexibility in program development and implementation is essential. Program development should be based on continuous evaluation and feedback from community and program staff.

The White Mountain Apache Tribe, working together with the Johns Hopkins University Center for American Indian Health, has

developed an important community-based suicide prevention effort. The White Mountain Apache Tribal Council enacted a resolution to mandate tribal members and community providers to report all suicidal behavior (ideation, attempts, and deaths) to a central data registry. For those who have made suicide attempts or were reported to be thinking about suicide, a community outreach visits by Apache paraprofessionals supervised by a clinical team from the Johns Hopkins Center for American Indian

Health is attempted. SAMHSA is currently supporting an evaluation of the effectiveness of a specialized Emergency Department linked intervention and in home coping skills curriculum for youth who have attempted suicide, as identified by the White Mountain Apache Tribe surveillance and community outreach system.

Clearly, a public health approach can prevent suicidal behaviors. But, as demonstrated by these examples, effective prevention requires the whole community coming together to address and overcome barriers and to follow through with a sustained effort.

The Ecological Model

As noted in the introduction to this chapter, the ecological model is one way to interpret the public health model. The ecological model has its origins in the observations of nature and the interrelationships among all living things and their environments. It acknowledges the cyclical nature of life and the necessity for interdependent relationships in creating a community. This relational worldview is a vital aspect to community-wide prevention efforts by AI/ANs. The ecological model is not new to AI/AN communities. It might even be said that AI/ANs and other aboriginal peoples were the first to truly live within and by this model, making it not so much an abstract theory as a way of life and of being in the universe.

In the ecological model, community members are seen not as separate individuals but as parts of a whole (see Exhibit 8). This model places the individual inside the family, which resides within the community and its culture, which, in turn, is part of society at large. Each level influences and is influenced by the other levels. Ideally, each level strengthens and nurtures the others. As in the public health model, the health of the individual is seen as a reflection of the physical, social, cultural, spiritual, and environmental status of the surrounding levels. All of these factors are interrelated in how they affect the health of the family, community, and society as well as the health of the individual.

The focus of the ecological model is on the interwoven relationships between individuals and their communities. While individuals are responsible for the choices they make that reduce their risk of illnesses and promote health, their choices largely are determined by their social environment, such as their community’s existing norms, values, and practices. As an example, alcohol and substance use—both of which are risk factors for suicide—are lower among youth who believe that their parents (i.e., the family as “community”) are more likely to disapprove of such behavior.111 Thus, mentally healthy individuals are created through families, communities, and a society that encourages mentally healthy behaviors.

As this model implies, prevention involves a systemic, holistic approach to addressing risk and protective factors for mental and other illnesses at all of these levels. In addition, successful prevention efforts become part of each level and gain from everyone’s energy and involvement. To illustrate, consider the experience of the Shuswap Tribe of Alkali Lake, in British Columbia, Canada, in reducing and preventing alcoholism. A very simplified case history and illustrations demonstrate how the ecological model applies

both to the increasing and decreasing use of alcohol and its consequences.

In the 1940s, the Shuswap Tribe was introduced to alcohol by non-Natives. At the same time, the government was removing a whole generation of Tribal children from their families and sending them to boarding schools. While the schools provided a general education, school-based efforts to erase Tribal language and practices created a form of racial/cultural self-hatred in the children.

The children also were exposed to widespread physical and sexual abuse. They returned to their communities damaged in mind and spirit.

These children had not been parented themselves; nor had they been able to internalize traditional values and practices of healthy family and community life. Because of these losses, this generation of Alkali Lake people was much more vulnerable to the culture of alcohol. Under the combined weight of growing alcoholism and a legacy of historical trauma, a once hardworking Tribe found itself and its children being destroyed by the poverty, hunger, sickness, violence, sexual abuse, and suicide that had become common on the reservation. By the early 1970s, an estimated 100 percent of all adults and many young people drank excessively.

Change came in the form of community healing and community action, led by the first few Tribal members to refuse alcohol. In 1972, one of these individuals was elected chief. Together, he and a core group of supporters banned alcohol on the reservation. They joined with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) to identify bootleggers. Tribal members who committed alcohol-related crimes were given a choice: treatment or jail. Non-native community members, including clergy, who opposed these reforms were asked to leave. As the use of alcohol became less accepted within the Tribe, more Tribal members who experienced alcoholism began to seek treatment.

Tribal leaders recognized that their growing success in reducing alcoholism would be strengthened by linking the community’s

continuing healing process to social and economic progress. They achieved this critical linkage through these strategies:

- Making a deliberate effort to revive traditional Native forms of spirituality and healing;

- Creating a variety of economic enterprises to provide employment for the growing numbers of individuals who did not drink alcohol (By 1985, Alkali Lake had achieved full employment—everyone who wanted a job had a job.);

- Introducing a wide variety of training opportunities that were connected to personal and community wellness and the

continued pursuit of social and economic improvements; and - Building community unity. Whenever Tribal members left the community for treatment, their children were taken care

of, their house was cleaned up and repaired, and there was a job waiting for them when they got back.

In short, the approach taken by the Shuswap Tribe to reduce and prevent alcoholism and its consequences demonstrates the ecological/public health model in action. Prevention efforts were both systemic and holistic. They went beyond a focus on the individual to include families, the Tribal community, and the larger surrounding society—which also had a stake in the outcome. The Tribal government, the justice system, businesses, and other local organizations all collaborated in both reducing risk factors

for alcoholism and in promoting personal and community wellness. The success of this approach to prevention is apparent. By 1979—just a few years after prevention efforts began—only 2 percent of Alkali Lake Tribal members were still drinking alcohol.

The Transactional-Ecological Framework

The transactional-ecological framework is another way of looking at how a public health approach can be applied to suicide prevention. While similar to the ecological model, this framework places greater emphasis on two key elements within a community. Within this structure:

- Disorders (e.g., suicidal behavior and/or substance abuse) result from deviations from normal developmental pathways and processes; and

- The roots of an individual’s disorder can be and often are outside of the individual.

From the perspective of this framework, the central objective of prevention programs is to create a community environment that helps young people avoid situations and behaviors that will start them along a pathway leading to negative outcomes. Prevention efforts will not focus on individuals or groups at risk or on a single behavioral disorder because such efforts can be seen as “victim blaming,” in which the individual alone is responsible for his or her difficulties. Instead, a community would focus its efforts on the elimination of broad-based environmental conditions that can lead its members to engage in any number of undesirable, interrelated outcomes (e.g., school failure and substance abuse) and not just on one specific outcome (e.g., suicide). The preceding

example of the Western Athabaskan Tribal Nation demonstrates the success of this approach for Native communities.

The points of intervention—or the opportunities to return individuals to normal pathways—can involve the reduction of risk factors, the improvement of protective factors, or both. However, as noted earlier, increasing the number of protective factors has proved more effective in reducing suicide attempts than reducing the quantity of risk factors.

Action-Planning Tools

The public health model is an evidence-based theory for picturing prevention. The following sections describe two tools that are available to communities in translating this theory into action.

SAMHSA’s Strategic Prevention Framework

The SPF has been shown to promote youth development, reduce risk-taking behaviors, build assets and resilience, and prevent problem behaviors across the lifespan. It is based on six key principles that are grounded in the public health approach. Because these principles are the foundation of the SPF process, they are described briefly first.

Guiding Principles of the SPF

- Prevention is an ordered set of steps along a continuum to promote individual, family, and community health, prevent mental and behavioral disorders, support resilience and recovery, and prevent relapse.

Prevention activities range from deterring diseases and behaviors that contribute to them to delaying the onset of disease and reducing the severity of their symptoms and consequences. This principle acknowledges the importance of

a spectrum of interventions that extend along the mental health continuum and involve all of the individuals and environments that affect a person’s mental health and well-being. - Prevention is prevention is prevention

It does not matter if the focus of prevention is on reducing the effects of cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, substance abuse, or mental illness—the common components of effective prevention are the same. In addition, prevention of any one disorder frequently helps to reduce another. As noted in an earlier discussion of the U.S. Air Force suicide prevention program, prevention of suicide also helped to prevent homicide and domestic violence. - Common risks and protective factors exist for many substance abuse and mental health problems. Good prevention focuses on the common risk factors that can be altered.

Family conflict, low school readiness, and poor social skills all increase the risk for conduct disorders and depression in young people. These disorders, in turn, increase a young person’s risk for substance abuse, delinquency, violence, and

other factors that may contribute to suicide. Alternatively, protective factors such as strong family bonds, coping skills, opportunities for school success, and involvement in community activities can foster resilience and lessen the influence of these risk factors. Effective prevention works to reduce common risk factors and enhance common protective factors. - Resilience is built by developing assets in individuals, families, and communities through evidence-based health promotion and prevention strategies.

Resilience is a person’s ability to cope with the frequent challenges that life presents. Youth who have positive relationships with caring adults, good schools, and safe communities develop optimism, good problem-solving skills, and other assets that help them deal with adversity and go through life with a sense of mastery, competence, and hope. - Systems of prevention services work better than service silos.

Working together, researchers and communities have produced a number of highly effective prevention strategies and programs. Implementing these strategies within a broader system of services increases the likelihood of successful, sustained prevention activities. Collaborative partnerships enable communities to leverage scarce resources, build greater capacity, and make prevention everybody’s business. - Baseline data, common assessment tools, and outcomes shared across service systems can promote accountability and effectiveness of prevention efforts.

A data-driven strategic approach that is adopted across service systems at the Federal, State, Tribal, community, and service delivery levels increases opportunities for collaboration and positive outcomes.

The SPF Process

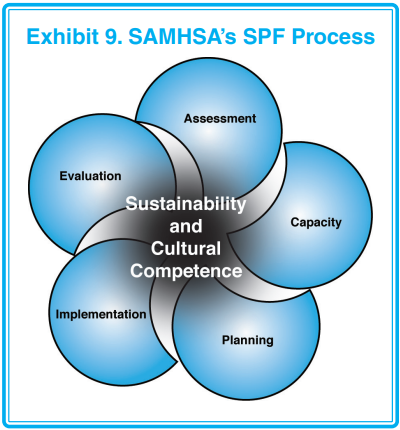

The SPF, just like the public health model, uses a five-step process to organize prevention efforts. As shown in Exhibit 9, the SPF process is circular rather than linear. It is designed to be a process of discovery rather than simply a process. Communities will experience a certain amount of back-and-forth between steps as new ideas or new threats to health emerge, goals are met,

and priorities change. At the heart of the entire process are cultural competence and sustainability of prevention activities.

Applying the SPF Process

The following section describes steps in the SPF process as they apply to suicide prevention by AI/AN communities. Additional information about the SPF is available at http://prevention.samhsa.gov/about/spf.aspx

- Assess the problem.

In this step, a Tribal community will develop a profile of the problem, its readiness to address the problem, and its resource needs. Common actions are to:

• Collect epidemiological data;

• Assess risk and protective factors, such as the magnitude of a substance abuse problem in or near the Native community;

• Assess Tribal/Village community assets and resources;

• Identify gaps in Federal and Tribal/Village services and capacity;

• Assess community readiness;

• Identify priorities; and

• Specify baseline data for the Tribe/Village against which process and outcomes can be measured. - Build the capacity to address these needs.

In this step, an AI/AN community will mobilize and build its capacity to address identified problems and gaps in service delivery. Capacity building activities may include:

• Convening Tribal/Village leaders and other community stakeholders;

• Building coalitions of Federal, State, local and Tribal/Village service providers; and

• Engaging Tribal/Village leaders and other community stakeholders to help sustain the activities. - Develop a strategic plan for addressing needs.

In this step, a community will develop a plan that will guide it in organizing and implementing the strategies that it believes will help it achieve its prevention goals. This plan also will help a community focus its resources on the group at greatest risk (e.g., adolescent males) and on issues of highest priority (e.g., mental health care services). The community can adjust its plan as new information becomes available or as it achieves its goals and objectives. - Implement evidence-based strategies with fidelity.

In this step, the community will select and implement programs that have proven effective in achieving the desired results. “Fidelity” in carrying out a strategy will be essential if a community is to achieve the same results. Fidelity refers to the degree to which a program or strategy is implemented as designed. For example, there is a loss of fidelity if a counseling program is supposed to have 10 sessions, but funding only is provided for 7 sessions. Loss of fidelity can result in a loss of effectiveness. To maintain fidelity and outcomes, key elements of a strategy should remain intact even when minor adaptations are made to meet cultural needs.

Communities should consult with the program developer in adapting programs, if possible. Often, a program developer will help a community identify the key elements of the program that are necessary to achieve the desired outcomes and to adapt other elements to ensure cultural effectiveness. - Monitor and evaluate.

This step involves monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of the prevention activities. In this way, a community can sustain those activities that are working or modify or replace those that are not. Although evaluation is presented here as the last step, it actually is a continuous process that should begin with the first step. Evaluation lets a community and funding agencies (if any) know how effectively the community has defined, and is responding to, suicide.

The SPF and Cultural Competence

Cultural competence is at the heart of the SPF process. A culturally competent program demonstrates sensitivity to and understanding of cultural differences in program design, implementation, and evaluation. Such programs:

- Acknowledge culture as a predominant force in shaping behaviors, values, and institutions;

- Acknowledge and accept that cultural differences exist and have an impact on service delivery;

- Believe that diversity within cultures is as important as diversity between cultures;

- Respect the unique, culturally defined needs of various populations;

- Recognize that concepts such as family and community are different for various cultures and even for subgroups within cultures;

- Understand that people from different racial and ethnic groups and other cultural subgroups are usually best served by persons who are a part of or in tune with their culture; and

- Recognize that taking the best of both worlds enhances the capacity of all.

The SPF and Sustainability

Like cultural competence, sustainability is an essential element of each step of the SPF. Sustainability refers to the process through which a prevention system becomes a community norm. Sustainability is vital to ensuring that prevention values and processes are firmly established, that partnerships are strengthened, and that financial and other resources are secured over the long term. Sustainability also encourages the use of evaluation to determine which elements of a prevention program, policy, or service need to be continued and supported to maintain and improve outcomes. Because sustainability has a major effect on outcomes, communities need to make it an important part of each component in the whole planning process. If, for example, a community has a goal of reducing underage drinking by 20 percent, the community needs to plan how it will continue programs that produce the desired outcome. Such planning should begin as early in the assessment process as possible.

American Indian Community Suicide Prevention Assessment Tool

The American Indian Community Suicide Prevention Assessment Tool was developed by the One Sky Center, a national resource center for American Indians and Alaska Natives. It is dedicated to improving the prevention and treatment of substance abuse and mental health disorders across Indian Country.

This tool is designed as a template for assessing risk and protective factors within a Native community. It also is helpful in identifying available and needed prevention resources. Aspects of community health, such as the economic status of the Tribe,

community readiness, and community self-help are integrated into a holistic evaluation of prevention opportunities. Some of the

suggested uses of this tool include internal program assessment and planning. Information collected during the assessment also can be used to prepare grant applications, or the entire tool can be an appendix to an application. A copy of the template is included in Appendix D: Decision-making Tools and Resources. Communities can download the tool free from the One Sky Center Web site at http://www.oneskycenter.org/education/publications.cfm

Engaging Community Stakeholders in Prevention

Successful prevention means that an entire community is involved in planning, carrying out, and evaluating a comprehensive plan. Consequently, it is vital that all of a community’s stakeholders be engaged in identifying both problems and solutions. Stakeholders usually are individuals within the community with the most “at stake” around a particular issue.

Stakeholders will vary from community to community. In suicide prevention, major stakeholders might include those who have been most affected by suicide, are in leadership positions, have direct access to youth and young adults, and have time and resources to invest in addressing the issue. Young people clearly should be involved in developing prevention efforts. Not only will they have an increased sense of their worth and belonging in the community, but they can also provide valuable insights into the challenges that their generation is facing.

Engagement takes leadership. Tribal or Village leaders can encourage participation by making suicide prevention a priority for the community. Another approach is for a concerned and committed group of stakeholders to appeal to their leaders for support.

Building a Community’s Capacity for Prevention

Although community capacity building was covered briefly in the section about the SPF process, this aspect of prevention deserves

further discussion. When people think about capacity building, they frequently think in terms of treatment programs, counseling, and other support services. Community capacity building, however, goes beyond formal services. It also means building people’s commitment and skills to address problems and identify and respond to opportunities to promote mental health. It means

recognizing the strengths that already exist within a community and making these strengths part of the solution. The emphasis of community capacity building should be on what is good and what already is working within the community. This approach has the added benefit of increasing a community’s sense of empowerment in charting a more promising future for itself and its children.

On the other hand, community capacity building should not occur in isolation. As recognized in the National Strategy for Suicide

Prevention, a comprehensive approach “requires a variety of organizations and individuals to become involved in suicide prevention and emphasizes coordination of resources and culturally appropriate services at all levels of government—Federal, State, Tribal, and community.” Prevention efforts need to be as broad and continuous as the threats to a community’s mental health and the opportunities to combat them are. The best way to build, maintain, and sustain such efforts is to engage as

many participants as possible in prevention.

Other ways in which community capacity building can increase the success of prevention plans are to:

- Use a variety of methods and a systematic approach;

- Emphasize collaboration and cooperation among community agencies;

- Recognize that any particular suicide prevention effort will be more successful if it is part of a broader community health and wellness vision;

- Understand that efforts by local people are likely to have the greatest and most sustainable impact in solving local problems and in setting local norms; and

- Remember that when community resources are tapped, efforts are more likely to be based on concepts and ideas that are ethnically and culturally appropriate for that unique community.

Capacity Building and Gatekeeper Training

Many communities are adopting gatekeeper training as part of their youth suicide prevention plan. Through gatekeeper training, teachers, natural peer helpers, and others who come in regular contact with young people are taught the warning signs of suicide and how to encourage someone at risk to seek help. Several gatekeeper training programs are described in Chapter 7: Promising Suicide Prevention Programs.

As effective as gatekeeper training may be in identifying young people at risk, it raises the issue of a community’s capacity to handle the increase in referrals for services that can result. For Tribal communities with limited access to behavioral health services, the question becomes “refer where?” Without some thought to this question, gatekeeper training may result in increased pressure on an already overwhelmed medical and behavioral services system. Whenever possible, a community needs to coordinate prevention efforts with local behavioral health and primary care systems to ensure that they are aware of these efforts and can plan for increased service demands. It may be possible for these systems to apply for funding for additional staff to meet demand.

As community awareness increases, so do referrals. One answer to this increase in demand for services may be found in a particular type of community capacity building. As part of the community’s overall prevention plan, first responders, nurses, outreach personnel, and various paraprofessionals could receive training that goes beyond the gatekeeper level. This could include triage, intervention, and supportive counseling. Again, triage training programs are described in Chapter 7: Promising Suicide Prevention Programs.

While there are costs associated with this additional level of training, it not only increases community capacity but also long-term sustainability. Where possible, Tribal and Village communities might seek partnerships and additional grants to address this need.

Appendix D: Decision-making Tools and Resources lists several guides for coalition building as well as tools for assessment, planning, and school-based program planning.

Conclusion

Decades ago, Lone Man (Isna-la-wica) of the Teton Sioux said, “I have seen that in any great undertaking it is not enough for a man to depend simply upon himself.” As illustrated by the public health model, an entire community must come together in protecting its children from suicide. Prevention success cannot be achieved by leaving this greatest of undertakings to one family, one institution, one level of government, or even one Tribe or Village. Furthermore, what is learned about prevention must be shared among all of those who would benefit from this knowledge.

Communities can strengthen their suicide prevention efforts by making use of tools that are based on the public health model. Such efforts provide a systematic way for communities to define the problem and develop an effective response. In carrying out prevention efforts, a community may find that it is more effective, as well as more cost-effective, to focus on promoting mental health as a way to reduce risk factors for suicide and prevent mental health problems from occurring in the first place.

The most important part of this process, however, is the involvement of all individuals and institutions with a stake in the mental health and well-being of the community. Just as the causes of the problem of suicide can be found within a community, so can the solutions. The broader the base of community involvement, the more opportunities for prevention. The more a community builds its capacity for action, the greater the potential for success. This is the true measure of community’s action—people talking, sharing, and working together for the good of all.