Confidentiality

Confidentiality often plays a role in providing health care to adolescents. When it comes to

alcohol use by patients who are minors, don’t let concerns about confidentiality deter you from

screening and intervening as needed. All of the major medical organizations and numerous

current laws support the ability of clinicians to provide confidential health care, within established

guidelines, for adolescents who use alcohol (Berlan & Bravender, 2009; Ford et al., 2004).

It is important to give your patients an assurance of confidential care. Studies show that with

confidentiality assurance, adolescents are more willing to seek health care (Ford et al., 1997),

whereas without it, those who engage in risky behaviors will often forego care (Lehrer et al.,

2007). In addition, research indicates that most parents favor confidential care for their teens, and

that education about privacy policies and teen risk-taking behaviors improves the opinions of

most parents who hold negative opinions about confidentiality (Hutchinson & Stafford, 2005).

This section provides a brief overview of patient rights and professional association guidance,

along with practical suggestions for screening adolescent patients for alcohol use while respecting

confidentiality and its limitations.

Patient rights

State laws govern minor patient rights to confidentiality of information shared with health care

providers about alcohol and drug use. Across States, laws vary on provisions, including the

definition of a minor (typically under age 18), the ability of a minor to consent to substance abuse

treatment, parental notification of treatment, and the disclosure of medical records. It is important

to be aware of specific laws in your State, which generally allow health care practitioners to

use professional judgment in determining the limits of confidentiality. For information about

your State’s laws, contact your State medical society. In addition, a summary of State minor

consent laws, including confidentiality and disclosure provisions, is available from the Center for

Adolescent Health and the Law (English et al., 2010; www.cahl.org).

Federal medical privacy rules established by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability

Act (HIPAA) allow adolescent health care providers to “honor their ethical obligations to maintain

confidentiality consistent with other laws” (Ford et al., 2004). For example, HIPAA only allows

parents to have access to the medical records of a minor child if that access does not conflict with

a State or other confidentiality law. If State or other laws are silent on this matter, clinicians can

exercise professional judgment in deciding whether to allow access (Ford et al., 2004).

Additionally, federally funded treatment centers are subject to the Code of Federal Regulations

(42 CFR Part 2), which offers different guidance from HIPAA. These regulations protect the

confidentiality of records on alcohol and drug use of minor patients. These records cannot be shared

with anyone—including a parent or legal guardian—without written consent of the minor patient.

Professional association guidance

Professional associations have produced helpful guidelines, policies, and background information

to help steer you through the complex framework of laws and issues related to minor consent,

privacy, and confidentiality. A sampling of guidance from several organizations is offered below;

visit your member association Web site(s) for the full picture, or visit the Center for Adolescent

Health and the Law Web site (www.cahl.org) for a policy compendium (Morreale et al., 2005).

“The most useful information will be obtained in an atmosphere of mutual trust and comfort,”

states the American Academy of Pediatrics (Kulig & AAP Committee on Substance Abuse, 2005).

To facilitate confidential care, the AAP recommends establishing a privacy policy and sharing it

with parents and children around the time of the 7- or 8-year-old checkup, or at least by the 9- or

10-year-old checkup (Hagan et al., 2017). Also around this time, and certainly by the 12-year-old

checkup, you should routinely set aside a portion of the visit to spend time alone with the patient

(Hagan et al., 2017). This sets the stage for regular private conversations between adolescents and

clinicians throughout the second decade.

Regarding the central question of how to involve parents in your patients’ care, the American

Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) advises health care providers to make a “reasonable

effort to encourage the adolescent to include parents or legal guardians in health-related

decisions” (AAFP, 2008). If you do not think parent involvement would be beneficial, however,

the American Medical Association (AMA) advises that “parental consent or notification should

not be a barrier to care” (AMA, Policy H-60.965). The Society for Adolescent Health and

Medicine (SAHM) concurs, stating that “participation of parents in the health care of their

adolescents should be encouraged, but should not be mandated” (Ford et al., 2004).

Of course, there will be times when you’ll need to consider breaking confidentiality and involving

parents (see page 28, “When is it appropriate to break confidentiality?”). As summarized by the

AAFP, “Ultimately, the judgment of the physician should prevail in the best medical interest of

the patient” (AAFP, 2008)

Practical recommendations

- Always explain your confidentiality policy: It can be very effective to explain your practice's confidentiality policy to both the patient and the parent at the same time.

For example:

- Direct to patient: : “I will be asking you some personal questions that I ask all of my

patients so I can take the very best possible care of them. Everything we say here will

be confidential, in other words, will stay between you and me, but within certain limits.

The exception is if you tell me someone is hurting you physically or sexually, or if

you are hurting or planning to hurt yourself or someone else, then we will have to tell

others and get them involved to help keep you or the other person safe.”

- Direct to parent: : “What your daughter/son says to me is confidential, but obviously

you are free to discuss any topics between yourselves at any time. If your daughter/

son is in immediate danger or needs further treatment, I will certainly inform you and

include you in any discussions.” - Establish private time for screening: : If you offer a paper or electronic screening tool

before the exam, then clearly communicate to the patient and parent that privacy is needed to complete the screen. If you ask the screening questions yourself, only do so when parents are not in the room. Because the initial screening sets the stage for later visits, establish private time, starting with the first screening. This way, you’ll avoid sending a message that you would disclose the content of these conversations to the parent in the future. - Establish private time for talking: It is important to establish a standard routine for

adolescent patients to spend part of each visit alone with the clinician. Typically, the visit

starts with both patient and parent present, then the clinician spends time privately with

the patient, and the end of the visit serves as a group wrap-up. The rationale for private

time is both developmental (that is, acknowledging the patient’s emerging autonomy and

encouraging him or her to acquire skills to get health needs met) as well as to encourage

open communication about sensitive health issues. In deciding when to establish private time for a given patient, take more than just the patient’s age into account. A physically mature or provocatively dressed 10-year-old, for example, may be more in need of an alcohol screen than some of your older patients. - Decide how and when to honor commitments to change: A key intervention goal for

patients who have begun drinking but are not in acute danger is to obtain a commitment to

stop or cut back drinking. With older adolescents, it is often best to maintain confidentiality

(if requested) after accepting the patient’s commitment to avoid risky behaviors. If your

patient refuses to commit, however, or if you doubt the sincerity of the commitment, you

may want to consider breaking confidentiality. Furthermore, if at followup visits you find

that a patient has not demonstrated a commitment to the agreed-upon plan or has escalated his or her use, you should also consider breaking confidentiality. This can be framed within a context of concern for the patient’s health and the need to get a trusted adult involved to facilitate getting the help or treatment the patient needs. - Keep followup visits confidential: You can maintain confidentiality even if your

patient’s alcohol use indicates the need for a followup visit. Many physicians schedule

the next appointment with a medical “hook,” such as the need to follow up for acne or an

immunization or to discuss medications or lab results. - Talk about referrals: If you need to refer patients for further treatment, you may need to

talk to them about breaking confidentiality to discuss the referral with their parents. This

may be relatively simple, because in most cases when your patient is drinking enough to

require a referral, the parents are already aware that their son or daughter is drinking. - Be aware of practice procedures that can break confidentiality inadvertently: These

may include appointment reminders and billing and reimbursement procedures. The SAHM

advises you to develop strategies to “provide appropriate confidential care within this

context where feasible” (Ford et al., 2004). Consider taking continuing education courses

that not only keep you abreast of confidentiality matters in general but also touch on issues

that may arise as electronic medical records become more prevalent. - Clarify risks of releasing medical records to parents: It is unusual for a parent to demand

access to a child’s medical record without first trying to get answers from the child or

health care provider. On the chance that a parent does request medical records containing

confidential information, it’s important to know your State’s laws about release. Typically,

minors should be able to control access to information about services for which they can

legally provide consent, such as alcohol use and treatment in many States. If you are not able to protect the release of medical records, then it’s important to make it clear, prior to release, that by reading any sensitive health information, the parent may compromise your rapport and ability to work with the child. It may make it more difficult to elicit honest and accurate information from your patient, who will have lost trust in you. Suggest that the parent reconsider the request.

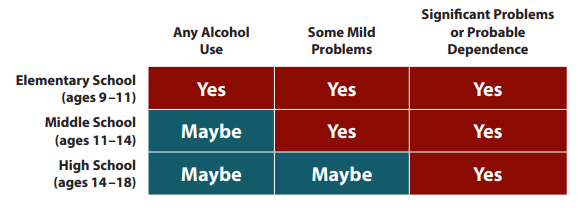

When is it appropriate to break confidentiality?

Your clinical judgment, together with your State’s minor consent laws, holds the answer. Below

are general guidelines related to age levels and alcohol use. In addition, consider the reported

alcohol-related behaviors and associated risks of significant injury, as well as the presence and

seriousness of any co-morbid conditions (such as depression, risk of suicide, poorly controlled

insulin-dependent diabetes).