Guiding Principles

Below are four overarching principles, lessons gleaned from previous public health emergencies, such as the HIV/AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 1990s. These principles serve as a guide for the design and implementation of effective overdose prevention strategies.

1. Know your epidemic, know your response

First advanced by UNAIDS as a guiding principle for global HIV prevention and control, the mantra “know your epidemic, know your response” originally spoke to the mismatch between strategy and reality that hindered HIV control efforts in the first years of the epidemic. In a 2008 Lancet article, Drs. David Wilson and Daniel Halperin championed the “know your epidemic, know your response” principle with their observation that “there is no single HIV Epidemic, but a multitude

of diverse epidemics” that differ according to “who gets infected and how.”

Similarly, opioid overdose is driven by a multitude of mechanisms and human experiences, and people may follow a variety of paths toward opioid misuse and overdose. The realities faced by people who use drugs may be common across regions or vary within tight social groups.

“Know your epidemic, know your response” reminds us that we must have a clear understanding of the causes and characteristics of local public health problems before we can know how to tackle them. It reminds us that our choices must be driven by evidence and data; that we must employ strategies we know to be effective; and that we must remain vigilant in maintaining a holistic and grounded understanding of who is at risk of fatal overdose, how that risk is constructed, and what can be done to reduce that risk as much as possible.

2. Make collaboration your strategy

Effective solutions to the opioid overdose crisis will only emerge from strong partnerships across governmental, legal, medical, and other community stakeholders. Collaboration between public health and public safety is especially important, as the impact of illicit opioid use and prescription opioid misuse is great on both of these fronts.

Overdose prevention strategies will only be successful if the role of each player is well designed, reasonable, and clear—and only if those players take on those roles in deliberate coordination with each other. Accomplishing this requires much more than sharing data and intelligence. The implementation of a proven public health approach such as a 911 Good Samaritan Law may be ineffective if law enforcement officers are not included in the planning and design of its implementation or if public safety protocols at the scene of an overdose are not discussed in tandem with the law. Similarly, the successful police takedown of a clinician or facility operating as an illegal “pill mill” may achieve long-term gains at the expense of creating short-term dangers if a public health strategy to support the patients suddenly cut off from this supply of opioids is not put into place ahead of time.

Effectively responding to the opioid overdose crisis requires that all partners be at the table and that

we “make collaboration our strategy” by ensuring that all community entities are able to fulfill their necessary roles.

3. Nothing about us without us

The phrase “nothing about us without us” reflects the idea that public policies should not be written

or put into place (officially or unofficially) without the direction and input of the people who will be affected by that policy. This mantra has been used by persons living with disabilities as they fought for recognition as independent persons who know their needs better than anyone else. It has been used by numerous at-risk groups in the U.S. to defend their place at the table in the planning of HIV prevention strategies.

In the context of today’s opioid overdose epidemic, “nothing about us without us” speaks to the fact that prevention strategies need to take into account the realities, experiences, and perspectives of those at risk of overdose. Those affected by opioid use and overdose risk should be involved in the design, implementation, and evaluation of interventions to assure those efforts are responsive to local realities and can achieve their desired goals.

4. Meet people where they are

Meeting people where they are requires understanding their lives and circumstances, what objectives are important to them personally, and what changes they can realistically make to achieve those objectives. For example, abstinence may not be immediately achievable by all who use illicit substances; however, many smaller changes may be feasible and could bring substantial benefit, such as reducing the spread of infectious disease, lowering overdose risk, and improving overall physical or mental health.

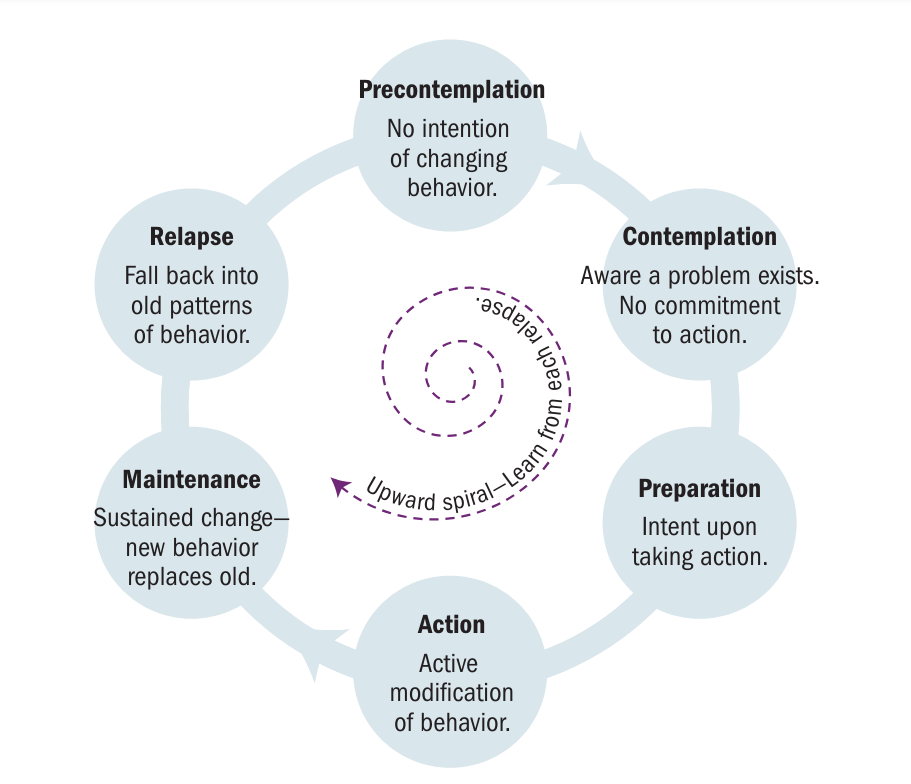

The Transtheoretical Model, also called the Stages of Change model, describes how such behavior

change often occurs. The model emphasizes the need to understand the experience of the person we are trying to reach in order to help them. To promote change, interventions must be provided that are appropriate for the stage in the process that people are in. The guiding principle of “meeting people where they are” means more than showing compassion or tolerance to people in crisis. This principle also asks us to acknowledge that all people we meet are at different stages of behavior change. Furthermore, recognition of these stages helps us set reasonable expectations for that encounter. For example, a person who has experienced an overdose who is precontemplative and has not yet recognized that their drug use is a problem may be unlikely to accept treatment when they are revived, but may benefit from clear, objective information about problems caused by their drug use and steps they can take to mitigate them. Unrealistic expectations cause frustration and disappointment for patients, providers, family, caregivers, and others touched by the event. Someone who is already preparing for action, however, may be ready for treatment, support, or other positive change. A positive, judgement-free encounter with first responders may provide the impetus and encouragement needed to get started. When we “meet people where they are,” we can better support them in their progress towards healthy behavior change. Recognizing the progress made as a person moves forward through the stages of change can help avoid the frustration that arises from the expectation that they will achieve everything at once.