Chapter 3: Breaking the Silence Around the Suicide Conversation

Introduction

The words of a First Nations Elder quoted above speak a powerful truth, particularly when applied to the silence surrounding the subject of suicide. Suicide, shrouded as it is in guilt, grief, anger, and the wrongful stigma of mental and substance abuse disorders, is one of the last great taboo conversations. The silence that may surround suicide, however, is not only dangerous but deadly. It affects the conversation that a community can have to address this issue, the conversation with an individual that can save a life, and the conversation with suicide survivors that can soothe their pain and prevent additional suicides. Only by having this conversation can a community begin to understand why some of its youth and young adults have chosen death. Only by having this conversation can a community then determine how it can help its children develop and maintain their hopes in themselves

and their lives.

Many of the barriers to having an open conversation about suicide are not unique to American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN)

communities. Various cultures around the world share in the difficulty of having this conversation and for many of the same reasons. Many people believe that initiating a conversation about suicide is too painful or is too intrusive and inappropriate. Some might consider this to be disrespectful of the dead. Even general grieving and mourning processes incorporate various culturally based practices and formalities. How does someone who has lost a loved one to suicide speak of it with others? How do the members of a community that have lost numerous young people to suicide speak of it openly in public meetings and with people outside of their own community? What do you say to a parent who has lost a child to suicide?

Although extremely difficult, such conversations are necessary in any community. Having said this, it is also important to acknowledge that some members of AI/AN communities may feel that there are religious or spiritual beliefs governing

the appropriateness of the suicide conversation. Many belief systems contain rules that guide how and with whom this conversation can take place. These are traditions to respect as part of creating a culturally appropriate suicide prevention plan.

This chapter focuses on breaking the silence surrounding suicide. It describes some of the barriers and myths surrounding a suicide conversation, including those that may be specific to AI/AN communities. This chapter also discusses why it is important for a community to overcome these barriers in its own way and within its own specific cultural context.

Some of these barriers and myths apply to conversations with individuals who may be considering suicide, with family and friends of someone who has completed suicide, and with communities that hope to prevent or are responding to suicides. How does a father ask his son if he is thinking about suicide? How might someone who is contemplating suicide express those feelings to a friend, parent, grandparent, or other adult? These, too, are difficult conversations, but ones that can save lives.

Barriers to the Suicide Conversation

In the following discussion, honor, historical trauma, and respect are labeled as barriers to a suicide conversation. This labeling is not intended to minimize their importance within AI/AN communities but rather to explain and help us understand why having a suicide conversation is so complex.

Underlying all of the barriers to the suicide conversation is language. As stated earlier, not all cultures use the same language, concepts, or values in discussing or understanding suicide. Consequently, the act of suicide, as well as its causes and prevention, may be spoken of in words and with a meaning not well understood within Native cultures. As a participant at the 2006 joint U.S. Canada conference on indigenous suicide stated, “We find ourselves forced to speak about our health with language and concepts that are not our own.” Finding ways in which everyone can understand and discuss suicide is critical to holding the suicide discussion and developing a prevention plan.

From Honorable to Forbidden Behavior

Suicide is viewed differently by various cultures, depending on the circumstances and the period of time. For some individuals, suicide is “forbidden in their traditional culture” and “to take one’s own life will cause the soul to remain in a state of distress.” Other cultures have accepted—and some may still accept—suicide as honorable behavior when a person’s death is:

• An atonement for shame they have brought onto themselves and their family;

• A protest against injustice;

• A form of martyrdom or a show of devotion for a great cause or religion;

• An exercise of a person’s right to choose how and when he or she will die;

• A show of bravery when one charges an enemy who has superior weapons; and

• A demonstration of selflessness, as when a person has gone far out into the snow to die so that others may share what little food is available and live.

Among AI/ANs, many of the stories, perspectives, and understanding of what has been labeled as suicidal behavior are deeply rooted in cultural history. Some deaths may be associated as easily with honor, sacrifice, and selflessness as with shame, grief, and depression. These contradictory and conflicting beliefs and emotions complicate the suicide conversation.

The concept of suicide as “honorable” needs to be acknowledged within its historical context and then reassessed and confronted as it applies to the lives of today’s youth and young adults.

Historical Trauma

As noted in the previous chapter, historical trauma is a risk factor for suicide that affects multiple generations. Many older members in the community may be reluctant to talk about this part of their past for a variety of reasons such as shame or not wanting to burden the young with their pain. Their silence might result from a reason as simple and basic as their not wanting to

reexperience that terrible pain.

As a result, it may be necessary for a community to address the impact of historical trauma prior to initiating or discussing any suicide prevention efforts. This conversation should only be undertaken with a full understanding

of how an open and direct conversation about current suicides may force some older AI/ANs to reexperience and reveal painful events of years past. One personal experience shared at the 2008 Tree of Healing Conference, presented by Camas Path of the Kalispel Tribe of Indians in Washington State, can provide some insight. An Elder who grew up in boarding schools told how young Native males frequently were found hanged to death in the school basement. These suicides always were reported by the school’s

administrators as “accidents” and never were discussed with the students. In this way, a whole generation may have been taught to respond to suicide with silence. Individual AI/AN communities will know best how to address the suicide conversation within the context of their own collective experience.

Guilt and Shame

Native Americans view children as gifts from the Creator. Their parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, Elders, and other members of the whole extended family and others are responsible for caring for and protecting that gift within the Sacred Circle of the community. What does it mean to all of these people to lose that gift to suicide?

As much as we try to understand the continuing negative impact of historical trauma on AI/AN communities and families, this single factor seems like an inadequate explanation as to why a young person dies by suicide. Despite the best efforts of their community and family, youth and young adults sometimes take their own lives. Those most closely related to the person may find it hardest to explore the reasons why.

For parents, this tragedy is often compounded by guilt, shame, and the haunting questions of “What did I do wrong?”, “Why didn’t I see this coming?”, and “Why didn’t my child come to me?” Any direct discussion about their child’s death may cause them to experience these painful feelings again. Many will feel additional reluctance to engage in a suicide conversation if their child’s suicide is linked to alcohol and substance abuse, particularly if they or their parents also struggle with the same disorder.

It also is common for parents who have lost a child to suicide to wonder what others in the community must be thinking. If they are asking themselves the “why” questions, then surely everyone else in the community must be doing the same. Again, parents may not want to talk with others within the community because of their feelings of guilt and shame. Some may not want to bring up the topic of suicide for fear of causing others to feel these emotions. Either way, the end result for the suffering family member is the same: isolation.

Having a suicide conversation can help a family member—or even a community—begin to heal from the tragedy of suicide. Even if someone does not know the proper words to say, he or she can take part in a conversation by listening. As one suicide survivor observed about her healing process, “Sometimes, I just needed someone to listen."

Personal Pain

The pain experienced by those who have lost loved ones to suicide is another barrier to having an open and public conversation about suicide. Some communities have many people who have lost a loved one to suicide, making a conversation about suicide even more difficult to start. Talking about suicide can be distressing both for the person who is talking and the person who is listening. Not talking about suicide is one way to try and avoid this pain.

With this barrier in mind, it is appropriate that the person wishing to hold a suicide conversation within an AI/AN community should first ask permission to bring up the topic. Permission can come in many forms, such as from the Elders within the community or the leadership of the community as well as from all those who attend the gathering and have lost a loved one. It also may be appropriate for the person who started the conversation to ask for forgiveness for causing painful feelings when the conversation is over. Time also must be available for those who wish to speak about loved ones who died by suicide, as it may be the first time anyone has asked them to share their stories.

One example of sharing occurred as a result of a Talking Circle conversation about suicide, which was facilitated by a community coordinator with Native Aspirations, a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) program to reduce violence, bullying, and suicide among AI/AN youth. An Alaska Native woman spoke of her isolation, saying that “after my son killed himself, no one talked with me about it, no one came to my house to comfort me. I am still hurt and angry about that.” Her son had been dead for 20 years. As painful as the memory must have been for her, she came to the gathering and spoke publicly of her pain. Her ability to finally share her story with the community let the healing within herself begin.

During the same Talking Circle mentioned above, an elderly man spoke of his good friend who had completed suicide when they were just out of high school. With tears in his eyes, he spoke as if he were sharing the pain and experience for the first time. Having been invited to speak of this experience, he felt he had received permission to share his pain.

Not every culture, however, relies on words to deal with grief and loss. For some, grieving involves participation in a specific traditional ceremony. Sharing a family’s loss may be expressed in an act as simple as offering condolences through a gift such as a pound of coffee. In attempting to open up a suicide conversation with a family who has lost someone to suicide, it is polite to inquire first as to what would be helpful or if they would like to talk about their loved one or about their grief. In any event, ask permission before beginning.

Collective Grief

Given what has been discussed about barriers thus far, it is not unusual to find a great deal of unspoken grief surrounding the topic of suicide within the community as a whole. Perhaps the specific ceremony was not performed, or the time period for talking about the loved one has passed.

Initial suicide prevention efforts either may be blocked by this silent grief or may provide community members with permission to release their grief in a flood of emotions. Either way, AI/AN community prevention plans may need to include community-based ceremonies and traditions to begin the healing of this collective grief. This may be accomplished through ceremonies such as the Wiping of the Tears or a Gathering of Native Americans (GONA).

The release of pent-up emotions is more likely to happen over time rather than at once. Questions arise as to how the community can have the suicide conversation in a way that respects and protects people experiencing grief. A primary question is: How can suicide prevention planning meetings and training sessions be conducted in a way that provides enough time so that once the wounds have been opened they are not left open when everyone goes home? To ensure that everyone who attends these gatherings are given support during the conversation, counselors or traditional healers may need to be present and willing to stay after the meeting to help the community begin to heal its collective grief.

Politeness and Respect

Politeness and respect may seem like strange barriers to a conversation about protecting the youth of a community. In any community, these qualities are valued as a necessity for community living. As Erving Goffman described in his early study of what has become known as “politeness theory:”

Politeness Theory and Suicidal Warning SignsSomeone who is contemplating suicide often will send warning signs to those around him or her, but these

As for individuals experiencing a suicidal crisis, vague or indirect calls for help helps protect them from their No matter how strong the politeness convention of a culture is, the value of life should be stronger. Politeness |

In any society, whenever the physical possibility of spoken interactions arises, it seems that a system of practices, conventions, and procedural rules comes into play which functions as a means of guiding and organizing the flow of messages. An understanding will prevail as to when and where it will be permissible to initiate talk among whom, and by means of what topics of conversations.

In many ways, these conventions help define “culture” and establish the rules for how community members will interact. These

conventions evolve over time and, while rarely written down, are passed from generation to generation. Although many members of a community and culture may not be able to list all of these conventions, they know it when they violate one.

Holding a suicide conversation challenges these conventions. It is a difficult conversation to have on both the personal level and on the community level. For example, we might be able to ask a sister or brother if they are having thoughts of suicide but not a parent or Elder. We might be able to talk with a close friend about thoughts of suicide or of a suicide in the family but not at a public meeting or with strangers. In addition, it may be considered rude and disrespectful to make others uncomfortable or embarrassed in a public setting or to speak publicly about suicide within the community without first having permission from an Elder. As important as these conventions are to social interaction, they can prevent the community from coming together and talking about the causes and prevention of suicide.

It falls on the community to resolve the issues presented by politeness and respect. Just as cultural differences occur between each Tribal community, different values are placed on politeness and respect. For prevention efforts to be successful, wever, each community must find its way to have a respectful conversation about suicide.

Stigma

The act of suicide is surrounded by stigma. Many religious denominations consider suicide a sin, and some previously did not allow a consecrated funeral for the “sinner.” Historically, suicide was reported as a crime—a practice that did not end in all States until the 1990s. We see this stigma in the language used to describe suicide: someone who takes his or her own life “commits suicide.” This wording carries the same social disapproval as when a person “commits” a sin or “commits” a crime. Consequently, those who have attempted suicide or survived the death of a loved one prefer the wording “completed suicide” or “died by suicide,” as is used in this document.

The stigma of suicide also affects the suicidal person and his or her family. This stigma can cause many families to suffer in silence and isolation and prevent them from receiving the support they need, particularly when another family member responds to the first suicide with his or her own suicide.

Some of the stigma that surrounds suicide can be positive. The idea that suicide is a sin or a crime against life prevents some people from attempting suicide. At the same time, this stigma can prevent a person experiencing a suicidal crisis from seeking the help he or she desperately needs. One 2007 survey of AI/AN adolescents who had thought about or attempted suicide identified “stigma” and “embarrassment” as common reasons for not seeking help. After a suicide completion or attempt, the stigma of suicide becomes a barrier to discussing why someone ended or tried to end his or her own life.

The stigma of suicide is compounded by the stigma associated with mental illness and substance abuse—the risk factors most commonly associated with suicide. It may be difficult for a community to have an open, comprehensive discussion about the causes and prevention of suicide before it first deals openly with the need to prevent and treat these two disorders.

Paul Quinnett, author of Suicide: The Forever Decisioned often proposes that clinics, schools, hospitals, and other public places post signs that say “Suicide Spoken Here. ”While such an action may seem extreme, it may be the kind of action needed to remove some of the stigma that surrounds a suicide conversation. Individuals should be able to speak without fear or shame about their suicidal thoughts and what may be causing these thoughts. When this is possible, they will find the care and support they need to

honor themselves and their lives.

Fear

A major barrier is fear—fear that talking to someone who appears at risk of suicide might push that person over the edge, fear that such a conversation might actually plant the seed for suicidal actions. If this fear of raising the topic of suicide with an individual exists, then how great is the fear of engaging an entire community in a discussion of suicide? This particular barrier will be addressed in greater detail later in this section, under Myths About Suicide.

Social Disapproval

The stigma attached to suicide sometimes extends to those in the community who have broken the code of silence around suicide

and are in the forefront of prevention efforts. Although these individuals have overcome their own reluctance, grief, and fear to speak openly about this sensitive topic, others in the same community may not have reached this level of openness or healing. As a result, they may feel anger towards the person who is making them feel uncomfortable. They may resent the attention

that a suicide conversation draws to risk factors within their community. In addition—out of fear or discomfort—they may avoid someone who seems unafraid of speaking to others about suicide and death.

Elders, healers, and others in the community can reach out to those who are engaged in suicide prevention by supporting and blessing their work. Suicide prevention is difficult but vital work, and those who engage in it need to be assured that they and their work are valued by their community. With leadership, engagement in suicide prevention can be a community-wide priority. For example, in January 2001, the White Mountain Apache Tribe became the first group in the United States to mandate community

wide reporting of suicide completions, attempts, and ideation.

Responding to Conversation Barriers

Many of the barriers to holding a suicide conversation overlap and compound each other. There is no easy or single solution to breaking the silence around suicide. Many Tribes and Villages, however, have faced this challenge successfully and are helping their children experience the joys of life. Some of the prevention activities being used by these communities are described later in Chapter 7: Promising Suicide Prevention Programs.

As difficult as it is to have the suicide conversation, it seems that not having it is no longer an option. The question is not

if a community should have conversation about suicide but how and when. It is the responsibility of each community to find the ways to overcome the barriers to the suicide conversation. Communities may want to invite a gathering of Elders to explore how suicide can be spoken of within the community. The results of this conversation may need to be shared with community members before any major prevention program is developed. The more people feel they have permission to talk, and the invitation, opportunity, and support to talk—with people who will listen—the more an open and productive conversation will flow.

Myths About Suicide

Several widely held myths about suicide interfere with a suicide conversation. Many people worry about what might happen if they talk about suicide. This concern is different from the worry about causing someone to feel guilt, shame, or pain, or being rude and disrespectful. Instead, this concern is grounded in the power of the spoken word. Within different AI/AN cultures, words have the power to call forth or create and to name or define. The person through which the words flow is the teller of history. Words are also about honor and the importance of giving one’s word to another.

The power of the spoken word raises many questions about a suicide conversation. Will speaking about suicide cause it to happen? Will it plant the idea in the mind of a young person who may have not otherwise thought about it? If suicide were never spoken of again, would suicides stop? These questions can create genuine concern about how, when, and under what circumstances a person can speak about suicide.

As important as it is to honor the belief in the power of words, it is equally important to be able to discuss suicide openly in order to develop a viable suicide prevention program. As noted in the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention, confronting the myths about suicide and suicide prevention is essential to creating an informed public and the kinds of social and policy changes that lead to greater investments in prevention efforts. Furthermore, “if the general public understands that suicide and suicidal behaviors can be prevented, and people are made aware of the roles individuals and groups can play in prevention, many lives can be saved.”

Everyone needs to become involved in dispelling the following myths so that a conversation around suicide can take place. This may include recognizing the importance of involving Tribal Elders, leaders, and healers in any suicide prevention effort. This may mean an opening and closing ceremony around the suicide conversation, gaining permission from Elders to speak of suicide, or both. Each community may find specific ways of addressing the belief in the power of words in order to begin the conversation.

Finally, while the following myths refer more to having a direct conversation with a potentially suicidal person than they have with community wide prevention efforts, it is still important to address them in this section. If not addressed, these myths might interfere with the involvement of many AI/AN community members in the prevention effort. These stakeholders might even be afraid that any suicide prevention effort might cause more harm than good.

Myth 1: Talking about suicide, especially with adolescents, will “plant” the idea.

Many adults find it difficult to believe that a young person, with a full life ahead, could be thinking about suicide. They fear that asking the person about suicide will only introduce it as a possibility. They wonder, “What does a question about suicide say to young people about our trust and belief in them and their future?", "Isn’t it Important to stay positive?”, and “What can or should I do if an adolescent admits to thinking about suicide?” It might be even more frightening to have our concerns and suspicions about their thoughts of suicide confirmed.

Truth: Talking with youth and young adults about suicide will not plant the idea in their heads.

This truth bears repeating because the “seed planting” myth is so powerful and pervasive that even some mental health professionals seem to accept it. First, AI/AN youth and young adults already are well aware of suicide from their experience and conversations with suicidal peers and from the media. In fact, they are more likely to feel relief that someone cares enough to ask. Starting the conversation about suicide may help them to feel less alone and isolated.

Second, the research rejecting this myth is overwhelming. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there is no evidence that youth who participated in general suicide education programs had any increase in suicidal thoughts or behavior. Instead, some studies indicate that these youth have decreased feelings of hopelessness and were less likely to believe that social withdrawal was an effective way to solve problems.

Third, numerous research and intervention efforts have been completed without any reports of harm. Finally, several evaluations of school-based suicide prevention programs show that adolescents are more likely to tell an adult about a friend who is suicidal or have reduced suicidal thoughts after being given information about suicide.

The most important reason for shattering this myth is that when suicide prevention programs are established in schools, they reduce the rates of suicide. Two long-term follow-up studies have demonstrated this fact. In various counties where suicide prevention programs were provided in nearly all of its schools over a period of years, youth suicide rates declined, while State rates

remained unchanged or increased for the same period of time.

It is important to note that school-based suicide prevention programs are not designed nor intended to focus exclusively on suicidal feeling, but instead are focused on help-seeking behaviors, knowing the warning signs, addressing the myths about suicide, becoming aware of school resources, and resolving to take action. Of equal importance is the need to ensure that all of the adults in the school have received training prior to introducing such training to the students. In this way, the adults can develop the necessary policies, procedures, and resources to respond to any increase in requests for help from the students.

Myth 2: No one can prevent suicide—it is inevitable

This fatalistic view of suicide is reflected in a belief that suicide has become so commonplace that it is to be expected. No one can do anything to prevent it. This false belief may be one of many responses to the high rates of suicide in a particular community. High suicide rates can numb the community and cause many people to want to shut down in grief. Community members can be so overwhelmed by loss that they feel helpless in finding opportunities to prevent more deaths. Accepting suicide as preventable also may create profound guilt. The question becomes, “Why couldn’t I prevent my loved one from killing himself/herself?”

Others see suicide as too complicated and mysterious to understand. Why would anyone reject life? This view becomes a barrier to prevention because it may seem futile to try to prevent what cannot be understood. Still others may see suicide as one individual’s response to his or her own unique personal problems. What can a community as a whole do to prevent suicide among diverse individuals?

Truth: Suicide is preventable.

According to former U.S. Surgeon General David Satcher, suicide is our most preventable form of death. And, as devastating as even one death by suicide in a community can be, most people, including AI/AN adolescents and young adults, do not die by suicide.

To help dispel the idea that suicide is inevitable, suicide prevention actions frequently focus on the positive aspects of living: strengthening families, developing in youth the skills that help them cope with life’s challenges, and building up a youth’s sense of self-worth. A focus solely on risk factors could simply perpetuate a feeling of helplessness in a community. In suicide prevention, the message must be one of hope for everyone in a community. Prevention is as much about strengthening what is good and working within a community as it is about correcting what may be threatening the health and wellbeing of its members.

The power of hope in preventing suicide cannot be over-estimated. An example of its power can be seen in clinical trials to test new medications. In some study designs, half of the group is given sugar pills while the other half is given the new drug. Up to 20 percent of the people taking the sugar pills may show improvement—because they believe that they will. This result is called the placebo effect. Suicide prevention is as much about instilling hope in life as it is about knowing what programs are effective and

implementing them.

Myth 3: Only the experts can prevent suicide.

This myth is based on the belief that suicide prevention is the work of therapists, physicians, psychologists, or other trained specialists rather than that of a community at large.

Truth: Prevention is the task of the whole community.

It seems logical that people who are considering suicide be seen by a professional. It is important, however, to distinguish between the treatment of a suicidal person and preventing suicide by engaging a person at risk in a suicide conversation. Everyone in the community needs to be involved in suicide prevention, from Tribal and Village leadership, to Elders, to the extended family, to teachers, and to youth and young adults themselves. Everyone can help to promote the mental health of youth as well as decrease factors that place them at risk of suicide. Everyone can be alert for signs that a young person may feel troubled. The idea that an entire community must come together to prevent suicide and how they can do so is discussed in more detail in Chapter 6: Community Action. According to Native American culture, children are the gift of the Creator and it is the responsibility of the entire community to care for and protect that gift.

Myth 4: Individuals who are considering suicide keep their plans to themselves, andthis secrecy makes prevention impossible.

This myth assumes that most people considering suicide do not want to be stopped.

Truth: Individuals considering suicide frequently give verbal, behavioral, and situational “clues” or “warning signs” before they engage in suicidal behavior

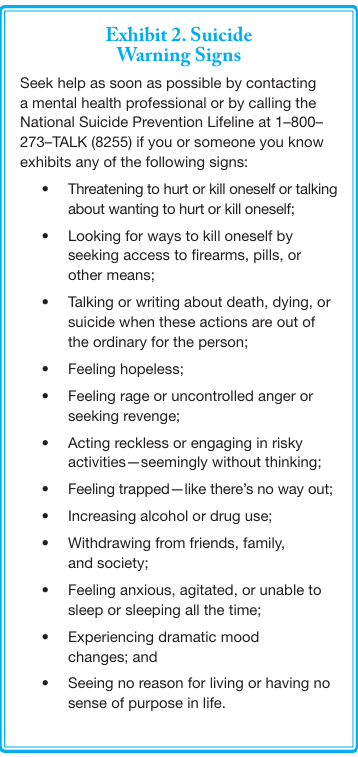

Commonly accepted warning signs are shown in Exhibit 2. However, further research is needed to identify any signs that may be unique to AI/AN youth and young adults.

As was discussed earlier in this chapter, many reasons exist as to why a suicidal person might “code” or disguise a warning that he or she intends to die. The reality is that most suicidal people tell someone about their intent during the week prior to their suicide attempt. This fact is the foundation for community awareness campaigns and general gatekeeper or peer training activities, which focus on identifying and referring at-risk individuals for treatment and supporting services. Gatekeeper training will be covered in greater detail in Chapter 7: Promising Suicide Prevention Programs.

Myth 5: Those who talk about suicide don’t actually go on to attempt it.

Truth: The opposite of this myth is actually true.

As described under Myth 4, verbal, behavioral, and situational clues and warning signs frequently precede suicidal behavior.

Myth 6: Once a person decides to die by suicide, there is nothing anyone can do to prevent it.

This myth is a variation of Myth 2, which is that no one can stop suicide or a person intent on suicide. The mistaken belief appears to be that, even if we could watch over a suicidal person every day, all day, he or she eventually would find a way to end his or her life.

Truth: Much can be done to prevent suicide.

It starts with asking someone who is showing suicidal clues and warning signs a simple question: “Are you thinking about suicide?” This question opens a conversation that can reduce a person’s feelings of isolation, anxiety, and distress and may lead them to seek help. Just asking the suicide question can reduce a person’s risk of suicide.

Also, as discussed under Myth 2, there are various reasons why someone would want to believe this myth. If a family has lost a loved one to suicide, and they are later told that suicide is preventable, what does that say about them? What could or should they have done to stop their loved one from dying? The idea that suicide is preventable can be very difficult to accept without experiencing guilt, shame, and anger if a suicide has occurred. In any prevention program, it is important to stress that people should not feel guilty about the past because of what they are learning just now in the present.

Conclusion

Talking about suicide is a difficult conversation that is complicated by barriers, myths, taboos, fears, and legitimate cultural considerations. As individuals, we might feel that suicide is beyond our abilities to prevent, yet we each have the power to speak and to act. Collectively, a community has incredible power when everyone comes together to talk, listen, plan, and act to help its children thrive.

It seems fitting to end this chapter as it began, with the words of the Canadian First Nations Elder:

Silence is dangerous when we pretend the

problem is not there . . . communication is a

healer to break the silence.