Chapter 7: Promising Suicide Prevention Programs

Introduction

Suicide prevention programs that show promise for American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) communities are those that have proven effective in reducing suicides and suicidal behaviors by enhancing protective factors, reducing risk factors, or both. While this definition seems simple enough, it raises questions about how the effectiveness of the program was measured and for whom it was effective. These questions have particular relevance in determining which prevention programs will work best within AI/AN communities, where research has been limited and the evidence supporting traditional or culturally based approaches may be anecdotal.

This chapter explores the issue of how evidence is defined and summarizes the difference between evidence-based and culturally based programs. The emphasis is on the need for all stakeholders to appreciate both of these approaches and to collaborate on building bridges between them. The issue is not which approach is best, but rather how we can learn from both in identifying, strengthening, and implementing AI/AN suicide prevention programs that work.

This chapter also identifies databases of evidence-based programs, such as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Registry of Evidence based Programs and Practices (NREPP) and its Suicide Prevention Resource Center’s (SPRC’s) Best Practices Registry. The chapter concludes with a discussion of two primary factors that a community should consider in selecting programs and descriptions of programs that hold promise for preventing suicides among AI/AN youth and young adults.

What Is Evidence?

Federal and State governments and other funding sources are placing increasing emphasis on the need for communities to implement evidence-based practices; that is, programs that have been shown through documented scientific evidence to achieve the desired outcome for the population of focus. As a result, it is becoming increasingly difficult for communities and organizations to receive funding for programs that have not met this standard. The rationale is easy to understand. Given limited prevention

dollars and the urgency of preventing suicides by AI/AN youth and young adults, it makes the most sense to invest in programs that have proven effective.

But how do we determine what is evidence? The move toward more evidence-based practices in recent years has elevated the standards within the field of suicide prevention, but it also has raised concerns among AI/AN researchers and community members as to whether traditional AI/AN community values and practices are being adequately addressed. Some researchers have argued that the emphasis placed on the use of evidence-based practices in AI/AN communities might lead to an abandonment of more traditional holistic approaches. These concerns are summarized in a report that was developed as a result of the National Alliance of Multi-Ethnic Behavioral Health Associations’ Consensus Meeting on Evidence-Based Practices and Communities of Color, which states:

The introduction of evidence-based practices (EBPs) would appear to be a solution to the misdiagnoses and poor outcomes that so many in diverse populations have encountered in the mental health system. However, it is equally as likely that EBPs could exacerbate and deepen existing inequities if they are implemented without sufficient attention to cultural competence and/or if policymakers fail to take into account the many practices within diverse communities that are respected and highly valued by these groups. Such practices may not be considered ‘evidence-based’ as they often lack access to research and evaluation funds that are critical for studying the efficacy and effectiveness of mental health interventions.

At the heart of these concerns is the perceived divide between evidence-based and culturally based programs.

Evidence-Based vs. Culturally Based Programs

SAMHSA’s National Registry of Evidence Based Programs and Practices (NREPP) defines evidence-based programs (EBPs) as:

Approaches to prevention or treatment that are based in theory and have undergone scientific evaluation. ‘Evidence-based’ stands in contrast to approaches that are based on tradition, convention, belief, or anecdotal evidence.

Culturally based programs, on the other hand, are those that are grounded in tradition and supported by “anecdotal evidence.” For example, AI/AN prevention specialists or other Tribal members may contend that a traditional approach to suicide prevention will work, citing as evidence the rarity of suicide within their long cultural history before they came in contact with Western cultures. Such evidence, which is grounded in the stories passed down within the Native oral tradition, has value but is difficult to substantiate. It also may be that the culturally based program has yet to be evaluated in a meaningful way.

These two approaches, however, are not mutually exclusive. One example of successful integration of evidence-based and culturally based practices can be found in the work of Terry Cross, an enrolled member of the Seneca Nation of Indians and the Executive Director of the National Indian Child Welfare Association. He describes a system-of-care model for AI communities in which:

Kinship networks and clan systems are being used as resources to provide respite care. Service providers and families are learning how traditional wellness concepts can facilitate a strengths-based approach to family harmony. Tools such as storytelling, the use of ritual and ceremony, rites of passage, and kinship support are being applied to a modern system of care.

Although this example refers to a treatment delivery system, similar opportunities exist to integrate evidence-based and culturally based approaches to prevention efforts.

As stated earlier, the issue is not which approach is best. Instead, it is how we can use both approaches to develop and implement suicide prevention programs that work best in AI/AN communities. SAMHSA recognizes that EBPs have not been developed for all populations, service settings, or both. For example, certain programs for AI/AN populations, rural or isolated communities, or recent immigrant communities that appear effective may not have been formally evaluated. Thus, they will have a limited or nonexistent evidence base. In addition, other programs that have an established evidence base for certain populations or in certain settings may not have been formally evaluated with other subpopulations or within other settings.

SAMHSA has responded to this challenge by encouraging grant applicants who propose a program that has not been formally evaluated to provide other forms of evidence that the practice is appropriate for the population of focus. Evidence for these practices may include unpublished studies, preliminary evaluation results, clinical (or other professional association) guidelines, findings from focus groups held with community members, and other sources.

In learning from culturally based programs, the focus may need to shift from why an AI/AN community believes a traditional approach will work to what its members can do to demonstrate its effectiveness. With this shift, the discussion can move to essential considerations such as how AI/AN communities can have a voice in determining how their traditional ways will be

measured, who will be doing the measuring, and how the knowledge gained will be shared with others and for what purpose.

Program Selection

A community needs to consider at least two factors in determining which strategy, or program, it will implement as part of its suicide prevention plan. The first is the population of focus. The second is the degree to which a program reflects or will need to be adapted to a community’s unique culture.

Population of Focus

All of the programs described in this document are intended to prevent suicide by AI/AN youth and young adults. The decision to be made is which program is most appropriate for the subgroup that is the focus of a suicide prevention plan. This is a multilayered decision. If the plan is to focus on school-aged youth, should the program involve all students within a school, just those who have been identified as at risk, or just adolescent males who are at high risk? Should a program focus all of its resources on school-based activities or should it direct resources towards families and the general community where the youth live?

All of the programs described in this document are intended to prevent suicide by AI/AN youth and young adults. The decision to be made is which program is most appropriate for the subgroup that is the focus of a suicide prevention plan. This is a multilayered decision. If the plan is to focus on school-aged youth, should the program involve all students within a school, just

those who have been identified as at risk, or just adolescent males who are at high risk? Should a program focus all of its resources on school-based activities or should it direct resources towards families and the general community where the youth live?

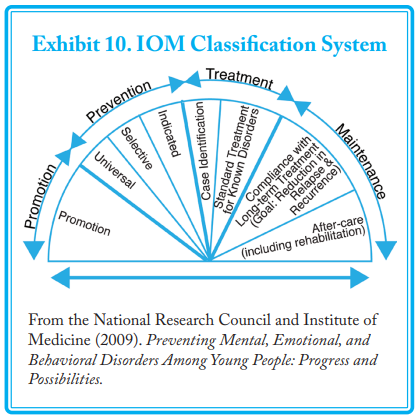

Universal strategies involve an entire population, which could be all members of a Tribe or Village or all youth within a school. As the term implies, universal strategies are broad-brush efforts that are intended to affect everyone who may be at risk. A universal strategy, for example, might be to increase the population’s access to counseling or to improve general social supports in the community, such as through after-school programs and youth centers. Other examples of universal strategies are:

- Public education campaigns;

- School-based suicide awareness and risk reduction programs, such as anti-drug use or anti-bullying programs;

- School-based programs that support the social and emotional development of youth;

- Means restriction, such as building barriers on bridges or reducing access to guns, poisons, ropes and items used for hanging, and other lethal means of self-harm; and

- Education programs for the media on reporting practices related to suicide.

Selective strategies address smaller groups within the total population who have a higher probability of suicide, and are meant to prevent group members from developing suicidal behaviors. This level of prevention includes:

- Screening programs to identify and assess at-risk groups;

- Gatekeeper training for adults or natural peer helpers so that they can identify individuals at risk of suicide and refer them to appropriate treatment or supporting services;

- Support and skill-building training for at-risk groups; and

- Crisis response and referral resources.

Indicated strategies address specific high-risk individuals within the population whose behavior shows early warning signs of suicide potential. Individuals who have some symptoms of a mental health problem, such as depression or hopelessness, or who are engaging in risky behaviors, such as alcohol and substance abuse, fit into this category. At this level, programs include:

- Skill-building support groups in high schools and colleges;

- Parent support training programs;

- Case management for individual high-risk youth at school; and

- Referrals to crisis intervention and treatment services.

Note that programs at all levels are designed to enhance protective factors and reduce risk factors. Ultimately, any comprehensive, community-based suicide prevention plan will need to address all levels of the IOM classification system.

Culturally Based and Culturally Sensitive

A second consideration in program selection is the degree to which existing programs reflect or may need to be adapted to a particular community’s culture. Some programs are culturally based, meaning that they were specifically developed by and for AI/ANs. Some of these programs may not, as yet, have the support of rigorous evaluation and thus may not be considered to be evidence based. Other programs are culturally sensitive. Such programs were developed for the general population, achieved some level of evidence, and then were adapted for AI/AN populations.

Both culturally based and culturally sensitive programs have potential strengths and limitations in their application to AI/AN communities at large. Culturally based programs were created around a specific culture. The more narrow the original cultural focus, the more difficult it may be for another community to achieve the same outcomes if its culture differs significantly. Programs that have been developed by and for AI communities in the lower 48 States, for example, may have limited applicability in AN Villages. Similarly, programs developed for one Tribe may not transfer well to another Tribe if the basis of the program is a tradition or practice unique to the original Tribe. However, if a particular culturally based program has reduced suicidal behavior in one community, then further investigation is called for. A careful evaluation of the program might identify a protective cultural aspect that may be transferable to another community.

On the other hand, culturally sensitive programs should not take so general a view of Native culture as to lack relevance for any Tribe or Village. Cultural sensitivity means more than adding a generic Native American face to program materials. Appropriate programs should be flexible enough to integrate the values, beliefs, language, and practices of a particular community without a loss of effectiveness.

The need to honor and respect Native culture in programs to prevent suicide by AI/AN youth and young adults cannot be overemphasized. Research indicates that strong cultural identification makes adolescents less vulnerable to risk factors for drug use and more able to benefit from protective factors than adolescents who lack this identification.120 In addition, having a purpose in life appears to help young people feel positively about their life and their ability to handle its challenges. In the worldview of Native culture, everything has a purpose, including trees, animals, and rocks. One of the most important developmental tasks for Native youth is to discover their own purpose, and AI/ANs have many culturally sanctioned practices (e.g., vision quest) for accomplishing this.

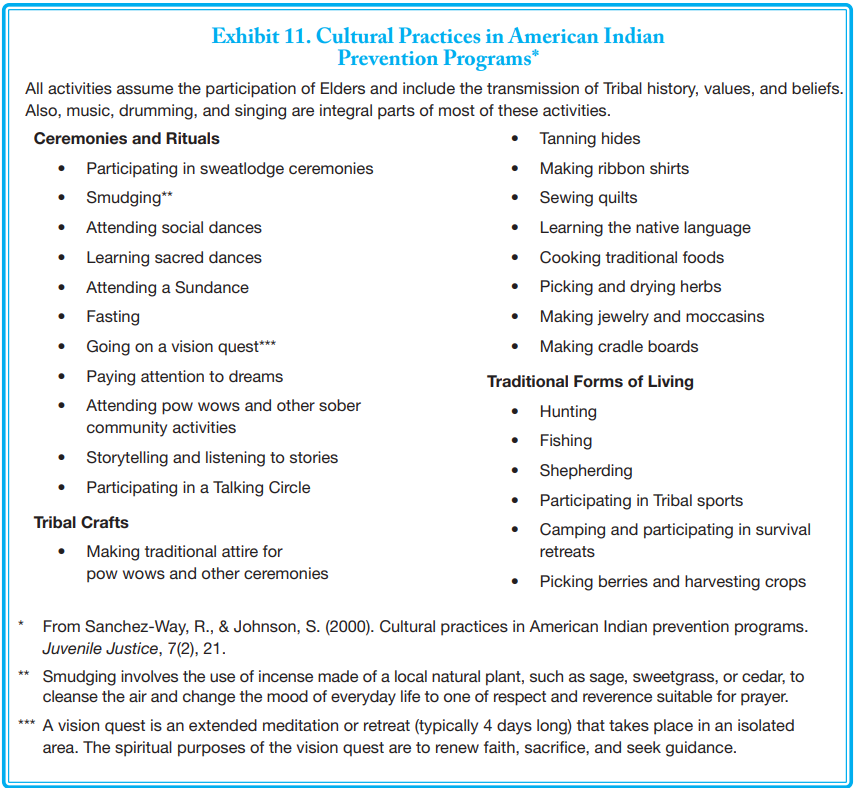

Exhibit 11 is a list of cultural practices that Native communities have been integrating into their approaches to preventing substance abuse, which is frequently present in suicide attempts. Ways in which programs might become more culturally

sensitive is to make them home- or family-based and deliverable by paraprofessionals.

Program Adaptation and Fidelity

Differences by Tribal group, culture, degree of Native ancestry, and reservation or urban location make it difficult to develop a general prevention approach for all Native youth and young adults. Thus, it may be necessary to adapt an existing program—whether culture centered, culturally sensitive, or not yet tried in AI/AN communities—to the language, beliefs, values, and practices of an individual community. SAMHSA’s principles of cultural competence for its Strategic Prevention Framework (see Chapter 6) can help guide this process.

At the core of program adaptation is the need to recognize a worldview that is consistent with AI/AN cultures, with worldview defined as “the collective thought process of a people or culture.”

According to Cross, in Understanding the Relational Worldview in Indian Families, there are two predominant worldviews globally: linear and relational.

- The linear worldview finds its roots in Western European and American thought. It is logical, time-oriented, and systematic, with cause-and-effect relationships at its core. To understand the world is to understand the linear cause and effect relationship between events.

- The relational worldview, sometimes called the cyclical worldview, finds its roots in Tribal cultures. It is intuitive, not time-oriented, and fluid. The balance and harmony in relationships between multiple variables, including spiritual forces, make up the core of the thought system. Every event exists in relation to all other events regardless of time, space, or physical existence. Health exists only when things are in balance or harmony.

In terms of adaptation, those who work with Native youth can show respect for the Native worldview when programs:

…build on young people’s connection to all other living entities; encourage and openly discuss their spiritual development; and

recognize the vital role played by Elders, aunts, uncles, and other blood or clan relatives and seek their involvement. We also

can make use of the outdoors, encourage generosity of spirit, incorporate more cooperative learning activities, respect the

individual, allow for a longer response time [in conversations], be more flexible with timelines, and respect that learning also can occur through listening and in silence.

Many AI/AN people are able to incorporate and move between these two worldviews.

The primary constraint in adapting programs is to ensure that fidelity is maintained even while some program characteristics are altered to allow for cultural input. It can be difficult to establish a balance between fidelity and adaptation. To ensure that a program addresses everyone’s real needs, there should be open communication between funders, staff members, and other community stakeholders during the implementation and ongoing evaluation of a suicide prevention plan.

Promising Program Databases and Descriptions

The following section identifies evidence- and culturally based programs for preventing suicide by AI/AN youth and young adults. Programs in the following list that have titles followed by two asterisks are included in SAMHSA’s NREPP. Programs marked with one asterisk have been rated as best practices by SAMHSA’s SPRC. Other programs are available through, or have been evaluated as being potentially useful to AI/AN communities by prevention specialists at the One Sky Center. SAMHSA has provided funding to this Center to identify, develop, and disseminate culturally sensitive materials for preventing and treating substance abuse and

mental health problems in Indian Country.

Many of the programs in the following list are school-based. Schools, in partnership with families, are in a unique position to promote the overall mental health of all young people as well as to identify those who may be at risk of suicide. Schools can directly address some risk factors for suicide, such as bullying and academic failure, within the context of improving school achievement. Youth also appear more likely to take advantage of services that are offered through a school rather than in other settings. This difference may be due to easy access or to a decrease in the stigma of seeking help. Other research has shown that a sense of connection or belonging to their school community has a strong, protective effect against suicidal thoughts

by youth. Furthermore, AI/AN communities often are geographically isolated and lack access to behavioral health services. School-based programs enable communities to overcome these challenges by centering the program and its services in the community.

The following programs focus specifically on suicide prevention. Other programs aimed specifically at promoting the mental health of youth (e.g., programs to strengthen family bonds) or to reduce any of the risk factors for suicide (e.g., programs to prevent and treat substance abuse and mental health problems) also may be effective in reducing suicide. It is beyond the scope of this document to include the broadest range of programs possible, but readers are encouraged to consider them as part of their suicide prevention plan.

SAMHSA’s NREPP, at http://www.nrepp.samhsa.gov, contains an extensive list of related programs. Other Federal agencies also maintain online databases. The U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, maintains a similar database—its Model Programs Guide—at http://www.dsgonline.com/mpg2.5/mpg_index.htm. This database offers evidence based programs to address a variety of youth problems, including delinquency; violence; youth gang involvement; alcohol, tobacco, and drug use; academic difficulties; family functioning; trauma exposure; sexual activity/exploitation; and other mental health issues.

Twelve Federal agencies make up the Interagency Working Group on Youth Programs. This work group promotes the achievement of positive results for at-risk youth by identifying and disseminating promising and effective strategies and practices that support youth. The group also encourages collaboration at the Federal, State, and local level, as well as with faith-based and community organizations, schools, families, and communities. It also has created a Web site on youth, at http://www.FindYouthInfo.gov, to

help interested citizens and decisionmakers plan, implement, and participate in effective programs for at-risk youth. Resources and available on the Web site include:

- A searchable database of evidence-based programs to address risk and protective factors in youth;

- Key elements of effective partnerships, including strategies for engaging youth;

- Helpful community assessment tools;

- Mapping tools that generate maps of local and Federal youth programs; and

- An overview of Federal programs that serve youth, technical assistance resources, and grant application guidelines.

National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices

SAMHSA’s NREPP is a searchable online registry of mental health and substance abuse programs that have been rated by independent reviewers. The purpose of this registry is to assist the public in identifying approaches to preventing and treating mental health and substance use disorders that have been scientifically tested and that can be readily disseminated to the field. This registry represents just one way that SAMHSA is working to improve a community’s access to information on tested interventions. One goal of this effort is to reduce the lag time between the creation of scientific knowledge and its practical application in the field.

NREPP, however, is meant to be a decision support tool and not an authoritative list of effective interventions. Being included in NREPP, or in any other resource listed in this guide, does not mean a program is recommended or that it has been demonstrated to achieve positive results in all circumstances. NREPP is a voluntary, self-nominating system in which program developers have chosen to participate. There always will be some programs that are not submitted to NREPP. Not all that are submitted are reviewed.

Programs in NREPP have been rated on two scales: Quality of Research and Readiness for Dissemination. Quality of Research ratings are indicators of the strength of the evidence supporting program outcomes. Each outcome is rated separately because interventions may target multiple outcomes (e.g., depression, feelings of hopelessness, drug involvement), and the evidence

supporting the different outcomes may vary. NREPP uses very specific standardized criteria to rate programs and the evidence supporting their outcomes. All reviewers who conduct NREPP reviews are trained on these criteria and are required to use them to calculate their ratings.

Each reviewer independently evaluates the quality of research for a program’s reported results using the following six criteria:

- Reliability;

- Validity;

- Intervention fidelity;

- Missing data and attrition;

- Potential confounding variables; and

- Appropriateness of analysis.

NREPP’s Readiness for Dissemination ratings summarize the amount and general quality of the resources available to support program use. Higher scores indicate more and higher quality resources are available. Readiness for Dissemination ratings apply to the program as a whole. Reviewers evaluate readiness according to three criteria:

- Availability of implementation materials;

- Availability of training and support resources; and

- Availability of quality assurance procedures.

Additional details about the NREPP review process are available at http://www.nrepp.samhsa.gov/review.asp

Suicide Prevention Resource Center Best Practices Registry

SAMHSA’s SPRC (described more fully in the following chapter) also maintains a searchable online database of suicide prevention

strategies. Its Best Practices Registry (BPR) is a collaboration between the SPRC and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP). The purpose of the registry is to identify, review, and disseminate information about best practices that address specific objectives of the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention. The BPR has three sections:

- Section I: Evidence-Based Programs describes programs that have undergone rigorous evaluation through NREPP or SPRC and have demonstrated positive outcomes;

- Section II: Expert and Consensus Statements summarizes the current knowledge in the field and provides “best practice” recommendations to guide program and policy development; and

- Section III: Adherence to Standards contains additional suicide prevention programs and practices, including awareness materials, educational and training programs, protocols, and policies that have been implemented in specific settings (as opposed to Section II statements, which offer general guidance to the field).

The three sections are not intended to represent levels of effectiveness. Instead, they include different types of programs and practices that have been reviewed according to specific criteria for that section.

SPRC no longer reviews program effectiveness, which now is conducted through NREPP. Programs that were reviewed previously by SPRC and are included in the BPR were evaluated according to 10 quality-based criteria: theory, intervention fidelity, design, attrition, psychometric properties of measures, analysis, threats to validity, safety, integrity, and utility. Additional information on the BPR is available at http://www.sprc.org/featured_resources/bpr/index.asp.

Promising Programs

The following programs are grouped according to their primary strategy for suicide prevention. The categories are:

- Life skills development;

- Screening;

- Public awareness/gatekeeper training;

- Counseling and support services; and

- Attempt response.

Each program description includes a note on the program’s actual or potential use in AI/AN communities.

Life Skills Development

Life skills development programs help young people develop the social and emotional skills that promote healthy relationships and self-esteem. At the same time, these programs strengthen their resilience in coping with the challenges of life.

American Indian Life Skills Development**

IOM classification: Universal

Population of focus: Male and female high school students, ages 14 to 19.

Description: American Indian Life Skills Development is a school-based suicide prevention curriculum designed to reduce suicide

risk factors and improve protective factors among AI adolescents.

The curriculum includes anywhere from 28 to 56 lesson plans covering topics such as building self-esteem, identifying emotions and stress, increasing communication and problem-solving skills, recognizing and eliminating self-destructive behavior, learning about suicide, role-playing around suicide prevention, and setting personal and community goals. The curriculum typically is delivered over 30 weeks during the school year, with students participating in lessons three times per week. Lessons are interactive and incorporate situations and experiences relevant to AI adolescent life, such as dating, rejection, divorce, separation, unemployment, and problems with health and the law. Most of the lessons include brief, scripted scenarios that provide a chance for students to problem-solve and apply the suicide-related knowledge they have learned.

Lessons are delivered by teachers working with community resource leaders and representatives of local social services agencies. This team-teaching approach ensures that the lessons have a high degree of cultural and linguistic relevance, even if the teachers are not AI/ANs or not of the same Tribe as the students. For example, the community resource leaders can speak to students

in their own language to explain important concepts and can relate curriculum materials and exercises to traditional and contemporary Tribal activities, beliefs, and values. A school counselor (typically of the same Tribe) serves as the onsite curriculum coordinator.

Application to AI/AN communities: This curriculum is the currently available version of the Zuni Life Skills Development curriculum. This original curriculum was first implemented with high school students in the Zuni Pueblo, an AI reservation with about 9,000 Tribal members located about 150 miles west of Albuquerque, NM. The American Indian Life Skills Development curriculum, an adaptation of the Zuni version, has been implemented with a number of other Tribes, with appropriate and culturally specific modifications. Adaptations of the curriculum have been developed for middle school students on a reservation in the Northern Plains area; for Sequoyah High School in Tahlequah, OK, a boarding school on the reservation of the Cherokee Nation that enrolls students from about 20 Tribes across the country; and for young women of the Blackfeet Tribe. The process of cultural adaptation incorporated into the program appears transferable to other populations.

2009 Cost: The American Indian Life Skills Development manual is available for $30 plus shipping and handling from the Chicago

Distribution Center (1–800–621–2736). Training for school staff costs about $3,000 for a 3-day training program conducted by the developer (exclusive of travel expenses).

Contacts:

For information about implementation or studies:

Teresa D. LaFromboise, Ph.D.

Senior Research Scientist

School of Education, Cubberley 216, 3096

Stanford University

Stanford, CA 94305

Phone: 650–723–1202

Fax: 650–725–7412

E-mail: lafrom@stanford.edu

Screening

Screening involves the identification of youth who may be at risk of suicide. Consent from parents of children younger than age 18 should be obtained before the children participate in a screening program.

Columbia University TeenScreen**

IOM classification: Universal

Population of focus: Male and female middle and high school students who may be at risk for suicide and undetected mental illnesses.

Description: The Columbia University TeenScreen program identifies middle school and high school-aged youth in need of mental

health services due to risk for suicide and undetected mental illness. The program’s main objective is to assist in the early identification of problems that might not otherwise come to the attention of professionals. TeenScreen can be implemented in schools, clinics, doctors’ offices, juvenile justice settings, shelters, or any other youth-serving setting. Typically, within a setting,

all youth in the age group of focus are invited to participate.

The program involves the following stages.

- Before any school-based screening is conducted, parents’ written consent is required. Parental consent is strongly recommended for screenings in non-school-based sites. Teens also must agree to the screening. Both the teens and their parents receive information about the process of the screening, confidentiality rights, and the teens’ rights to refuse to answer any questions they do not want to answer.

- Each teen completes a 10-minute paper-and-pencil or computerized questionnaire covering anxiety, depression, substance and alcohol abuse, and suicidal thoughts and behavior.

- Teens whose responses indicate risk for suicide or other mental health needs participate in a brief clinical interview with

an onsite mental health professional. If the clinician determines the symptoms warrant a referral for an in-depth mental health evaluation, parents are notified and offered assistance with finding appropriate services in the community. Teens whose responses do not indicate a need for clinical services receive an individualized debriefing. The debriefing reduces the stigma associated with scores indicating risk and provides an opportunity for the youth to express any concerns not reflected in their questionnaire responses.

Application to AI/AN communities: The TeenScreen program has been studied in a variety of school settings and with students of diverse ethnicity. The program also has been implemented in foster care, primary and pediatric care, shelters, drop-in centers, and residential treatment facilities. Although its use in Native communities is unknown, the program is an option for AI/AN communities.

2009 Cost: Costs involved in implementing TeenScreen include staffing (screener, clinician, case manager), supplies and equipment (computers, headphones, printers, photocopies), and mailing. Costs will vary by site. The program manual includes a budget planning exercise. At this time, the developers of TeenScreen offer free consultation, training, and technical assistance to qualifying communities that wish to implement their own screening programs using the TeenScreen model.

Contacts:

Web site: http://www.teenscreen.org

For information about implementation or studies:

Director

Columbia University TeenScreen Program

1775 Broadway, Suite 610

New York, NY 10019

Phone: 212–265–4453

Fax: 212–265–4454

E-mail: teenscreen@childpsych.columbia.edu

QPR Institute Suicide Triage Training/QPRT Suicide Risk Assessment Training

IOM classification: Selective, Indicated

Population of focus: Any person at risk of suicide

Description: The QPR (Question, Persuade, Refer) Institute is a multidisciplinary training organization with a primary goal of providing suicide prevention educational services and materials to professionals and the general public. The QPR Institute has developed an 8-hour QPR Suicide Triage Training Course for all “first responders,” including crisis line workers, law enforcement, firefighters, emergency medical technicians, clergy, case managers, correctional personnel, school counselors, residential staff, and

others who come in contact with people at risk for suicide.

The QPR Institute also offers the QPRT (Question, Persuade, Refer, Treat) Suicide Risk Assessment and Training Course. This course is an award-winning suicide risk assessment training program developed by clinicians for clinicians. The QPRT Suicide Risk Assessment and Training Course is for all primary health care professionals, counselors, social workers, psychiatrists, psychologists, substance abuse treatment providers, clinical pastoral counselors, and licensed and certified professionals who evaluate and treat suicidal persons.

Application to AI/AN communities: The QPR Institute, Eastern Washington University, and Camas Path, which is a Tribally chartered entity of the Kalispel Tribe of American Indians, have collaborated to offer both the QPR Suicide Triage Training Course and the QPRT Suicide Risk Assessment and Training Course online, with or without college credit. Courses can be accessed through Eastern Washington University at http://www.ewu.edu/x40902.xml.

2009 Cost: Cost of training ranges from $125 for non-credit or continuing education credits to $229 for Eastern Washington University credits.

Contacts:

Web site: http://www.qprinstitute.com

For program information:

QPR Institute

P.O. Box 2867

Spokane, WA 99220

Phone: 509–536–5100 or 1–888–726–7926 (toll-free)

Fax: 509–536–5400

E-mail: qinstitute@qwestoffice.net

Public Awareness/Gatekeeper Training

A gatekeeper is someone in a position to recognize the warning signs that someone may be contemplating suicide. According to the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention, potential gatekeepers include parents, friends, neighbors, teachers, ministers, doctors, nurses, office supervisors, squad leaders, foremen, police officers, advisors, caseworkers, firefighters, and many others who are in a position to recognize someone at risk of suicide and refer them to services.

Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST)*

IOM classification: Universal

Population of focus: Any individual at risk of suicide.

Description: ASIST is a 2-day workshop designed to teach the skills that enable an adult to competently and confidently intervene with a person at risk of suicide. Developed by LivingWorks, Inc., the workshop is intended to help all caregivers (i.e., any person in a position of trust, including professionals, paraprofessionals, and laypeople) become more willing, ready, and able to help persons at risk. The workshop is suitable for mental health professionals, nurses, physicians, pharmacists, teachers, counselors, youth workers, police and correctional staff, school support staff, clergy, and community volunteers.

Workshops are 14 hours long and are held over 2 days. The ASIST curriculum includes suicide intervention skill development, confidential and trainer-facilitated small-group learning environments, established trainer protocols to address vulnerable or at-risk participants, knowledge of local resources that can be accessed, consistent use of positive feedback, a blend of larger group experiential challenges and the safety of small-group opportunities to test new skills, no-fault simulation exercises, and the use

of adult learning principles.

Workshops are delivered to a maximum of 30 participants by a minimum of two trainers. Almost 2,000 ASIST workshops are conducted annually. In addition, a train-the-trainer program is available so that organizations can have their own trainers.

Application to AI/AN communities: The ASIST program has been implemented at several Native sites, both in reservation and

urban settings.

2009 Cost: ASIST training is provided by LivingWorks Education, Inc., of Alberta, Canada. The average program cost is $175

(Canadian) per person, which includes program materials. The cost will vary depending on the availability of trainers and other circumstances. Visit the Web site for a schedule of upcoming training.

Contacts:

Web site: http://www.livingworks.net/AS.php

For program information:

LivingWorks Education, Inc.

P.O. Box 9607

Fayetteville, NC 28311

Phone: 910–867–8822

Fax: 910–867–8832

E-mail: usa@livingworks.net or info@livingworks.net

Lifelines*

IOM classification: Universal

Population of focus: All students in a school, ages 12 to 17.

Description: Lifelines is a school-based prevention curriculum comprised of four 45-minute lessons. Lesson content includes:

• Information and attitudes about suicide, help seeking, and school resources;

• Discussion of warning signs of suicide and role-playing exercises for students who may encounter a suicidal peer (with an emphasis on seeking adult help); and

• Two videos, with one that depicts appropriate and inappropriate responses to a suicidal peer and one that documents the actual response of three 8th-grade boys to a suicidal peer after they had participated in Lifelines

The program also includes model school based policies and procedures for responding to at-risk youth, suicide attempts, and suicide completions; presentations for educators and parents; and a 1-day workshop to train teachers in the curriculum.

Application to AI/AN communities: The Lifelines program was studied in two suburban, middle-class schools in the Northeast, with positive outcomes. Although its use in Native communities is unknown, the program is an option for AI/AN communities.

2009 Cost: The Lifelines curriculum manual is available from Rutgers University for $45.

Contacts:

Rutgers University

Graduate School of Applied and Professional

Psychology

152 Frelinghuysen Road

Piscataway, NJ 08854

Phone: 732–445–2000, ext. 109

Native H.O.P.E. (Helping Our People Endure)

IOM classification: Universal

Population of focus: All Native youth.

Description: Native H.O.P.E. is a curriculum based on the theory that suicide prevention can be successful in Indian Country when Native youth become committed to breaking the “code of silence” that is prevalent among all youth. The program also is premised on the foundation of increasing “strengths” among Native youth as well as increasing their awareness of suicide warning signs. The program supports the full inclusion of Native culture, traditions, spirituality, ceremonies, and humor.

The 3-day Native H.O.P.E. youth leadership curriculum takes a proactive approach to suicide prevention. Training provided to natural peer helpers is designed to build their capacity and awareness to help youth through referral and support. Participants are taught to:

- Show they care by listening and acknowledging the other person’s pain;

- Make the person aware that he or she does have choices;

- Get peers at risk to a counselor or other source of health support; and

- Set limits on their natural helper role in the peer counseling process.

This program also is used to train local community members to be facilitators who encourage Native youth to take a leading role in prevention. A key to mobilizing peer counseling programs for Native youth is to identify and train adults from their communities who will be committed to wellness. These adults also will assist their youth in leadership development.

Application to AI/AN communities: This curriculum was piloted in the Billings, MT, area and through the Indian Health Service

(IHS) National Suicide Prevention Network in Standing Rock, ND and Red Lake, MN.

2009 Cost: The youth manual and facilitator guide are available free of charge through the One Sky Center and may be downloaded from http://www.oneskycenter.org/education/documents/NativeHOPEYouthManualCoverandIndex.pdf.

Contacts:

Web site: http://www.oneskycenter.org

For program information:

One Sky Center

Oregon Health & Science University

3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Road, GH 151

Portland, OR 97239

Phone: 503–494–3703

Fax: 503–494–2907

E-mail: onesky@shsu.edu

QPR Gatekeeper Training

IOM classification: Universal

Population of focus: Any person at risk of suicide.

Description: QPR is an acronym for Question, Persuade, Refer—three steps that a person can take in helping to save a life. Topics covered by the online program are:

- How to get help for yourself or learn more about preventing suicide;

- Common causes of suicidal behavior;

- Warning signs of suicide;

- How to “Question, Persuade, and Refer” someone who may be suicidal; and

- How to get help for someone in crisis.

Course participants receive resources and a certificate of completion after completing a post course survey and evaluation and passing a 15-item quiz. The online course takes approximately 1 hour to complete.

Application to AI/AN communities: The QPR training content identifies current resources and Web sites related to AI/AN suicides, including current research data. The Aberdeen Area IHS adapted the QPR suicide triage method by incorporating Native American scenarios and actors.

2009 Cost: An online course offered through QPR is $29.

Contacts:

Web site: http://www.qprinstitute.com

For program information:

QPR Institute

P.O. Box 2867

Spokane, WA 99220

Phone: 509–536–5100

Toll-free: 1–888–726–7926

Fax: 509–536–5400

E-mail: qinstitute@qwestoffice.net

Signs of Suicide (SOS)*

IOM Classification: Universal

Population of focus: All students within a high school.

Description: SOS incorporates two prominent suicide prevention strategies into a single program, combining a curriculum that aims to raise awareness of suicide and its related issues with a brief screening for depression and other risk factors associated with suicide.

This is a 2-day secondary school-based intervention. The basic goal of the program is to teach high school students to respond to suicide as an emergency, much as one would react to the signs of a heart attack. Students view a video that teaches them to recognize signs of depression and suicide in others. They learn that the appropriate response to these signs is to acknowledge them, let the person know they care, and tell a responsible adult (either with the person or on that person’s behalf). Students also

participate in guided classroom discussions about suicide and depression. For screening, students self-complete the SOS student screening form. A parent version of the screening form is provided for parents to use in evaluating possible depression in their children.

The intervention strives to prevent suicide attempts, increase knowledge about suicide and depression, and increase help-seeking behavior. Schools should be prepared to respond to an increased number of referrals for depression and suicide.

Application to AI/AN communities: The SOS program has been administered in more than 1,000 high schools and with culturally diverse students. Program effectiveness has been studied in urban settings, and efforts currently are underway to evaluate its effectiveness in suburban and rural populations. Although its use in Native communities is unknown, the program is an option for AI/AN communities.

2009 Cost: Teachers implementing the program will require 1 to 2 hours of training. The program also will require a site coordinator (usually a counselor). Program resources are provided through Screening for Mental Health for $300 for the high school kit, which includes materials for 300 students, parents, and school staff. (A middle school kit also is available for the

same cost.)

Contacts:

Web site: http://www.mentalhealthscreening.org

For program information:

Screening for Mental Health, Inc.

One Washington Street, Suite 304

Wellesley Hills, MA 02481

Phone: 781–239–0071

Fax: 781–431–7447

E-mail: highschool@mentalhealthscreening.org

Future Program Development

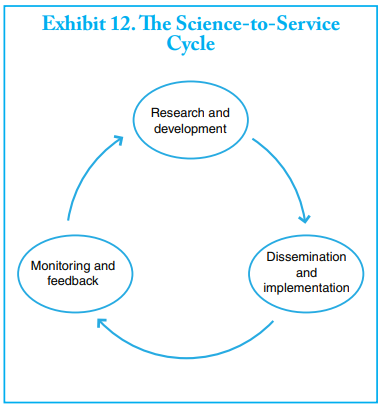

Research into programs that hold promise for AI/AN communities is expanding, bringing hope to many Native communities that solutions can be found that have both science and culture as their foundation. This research is an evolving process. The development of prevention programs that work is similar to life itself in that it is a cycle. Within the scientific community, this is referred to as the science-to-service cycle (see Exhibit 12), in which programs are developed, tested, and improved in response

to how effectively the program worked for the people being served. Far more feedback is needed from individual AI/AN communities on what they need and how well an existing program worked, given their own unique culture and values.

One potential bridge between program development that is evidence-based or culturally based may be through what is called practice-based evidence. This approach is gaining ground in many sectors because it emphasizes the study of what frontline people actually are doing to determine what is working. Practice-based research represents a significant shift in how research is conducted, including what is to be measured as evidence of effectiveness. It provides a greater voice to the people who actively engage in prevention and are applying practices that they believe are working. This practice-based approach may evolve into what the American Indian Policy Center calls “reality-based research.” As described by the Center, this approach:

… reflects the reality of American Indians and tells their stories, from an Indian point of view and from an Indian oral history standpoint. This reverence for oral history is particularly important because American Indian societies are based on oral tradition. Oral tradition preserves history, language and culture for American Indian communities. Using a method of research which respects and incorporates such basic tenets of a people’s culture makes our research more meaningful to Indian communities. In the past, Indians had a high distrust for researchers…. This ability to communicate with Indian communities and their leaders adds a critical component toward capacity building and self-empowerment of American Indian communities.

Another important aspect of engaging AI/AN communities in future program development and evaluation is the use of community-based participatory research. As the name implies, this form of research may involve the community in all aspects of the process, from determining what is to be studied to how the information is to be used. Under this approach, community-based

organizations—such as a Tribal government— play a direct role in the design and conduct of the research study by:

- Bringing community members into the study as partners, not just as subjects;

- Using the knowledge of the community to understand health problems and to design activities (i.e., programs) to improve health care;

- Connecting community members directly with how the research is done and what comes out of it; and

- Providing immediate benefits from the results of the research to the community that participated in the study.

Perhaps the best way to characterize the principle of participatory research is “research which recognizes the community as a social and cultural entity with the active engagement and influence of community members in all aspects of the research process.” The best programs will emerge from the broadest possible involvement of all members of a community in developing, implementing, evaluating, and improving prevention programs.