Chapter 4: Responding to Suicide

Introduction

The loss of a loved one by suicide is shocking, painful, and unexpected. Survivors, including whole communities, may experience a broad range of emotions including denial, anger, blame, guilt, helplessness, and confusion. One of the dangers of a suicide is that others in the community may be so overwhelmed by these emotions that they too try to take their own life. This situation is referred to as suicide contagion and, when it occurs, can be just as deadly to a community’s well-being as the spread of other

deadly viruses.

This chapter focuses on how a community might respond when tragedy does occur — when one of its youth or young adults takes his or her own life. It also describes actions that an American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) community might take to reduce the risk of additional suicides or suicide attempts. Directions on how to request an emergency response team through the Indian Health Service (IHS) are given.

Because a community is the sum of its individual members, this chapter begins with a discussion of how a community might comfort suicide survivors, who are those most affected by another person’s suicide or suicide attempt.

Next, the chapter describes how a community might develop a planned response to suicide contagion, to which youth and young adults appear most susceptible. The roles of the media, emergency health care providers, and suicide survivors and suicide attempt survivors in reducing the possibility of suicide contagion also are presented. The final section of the chapter describes Federal emergency response resources available to Tribes and Villages affected by suicide.

Responding to Suicide Survivors

For every suicide there are at least six survivors, which may be a conservative estimate. This most probably is the case for AI/AN communities because the number of suicide survivors usually refers just to blood relatives, significant others (e.g., spouse), or close

friends. It does not take into account the interconnectedness of relationships within Tribes and Villages or the complex and extensive relational network of a culture that sees others as all my relations. When considered within the AI/AN worldview, the number of survivors to a suicide might be closer to a range of 25 to everyone in the community and beyond. In a small Alaska Village of 500 to 800, all members conceivably could be considered survivors. Another way to understand the full impact of

suicide on AI/AN communities is to expand the concept of survivors to include those affected by a loved one’s suicide attempt. Although estimates for Native Americans, in general, are not available, one survey of Bureau of Indian Affairs schools suggests that 16 percent of AI/AN youth had attempted suicide in the preceding year.

While experiencing relief that their loved one is still alive, these individuals may experience many of the same feelings of pain, guilt, shame, and fear as those whose loved one did not survive. They also may be troubled by many of the same questions, such as “How could this happen?”, “Why didn’t he or she come to me?”, or “Why didn’t I see this coming?” When you include suicide attempt survivors with the numbers of suicide survivors, it is not difficult to imagine that the majority of AI/ANs have been directly and personally affected by suicide and suicidal behavior within their communities.

The emotional turmoil felt by those affected by a suicide or suicide attempt can be intense, complex, and long-term. These feelings may be compounded by the preexistence of historical trauma. Feelings of isolation also may complicate the grieving process and impede healing. Survivors of suicide often feel abandoned at a time when they desperately need unconditional

support and understanding.

There is no timeline for grieving. Those around the survivor may help most when they:

• Accept the intensity of the survivor’s grief;

• Listen with their hearts;

• Avoid simplistic explanations and clichés;

• Show compassion;

• Respect the survivor’s need to grieve;

• Understand the uniqueness of suicide grief;

• Are aware of holidays and anniversaries;

• Are aware of support groups;

• Respect the person’s faith and spirituality; and

• Work together as a helper for the survivor.

Grief work is a culturally specific process that each person experiences in his or her own way and at his or her own pace. The way in which each community and its members respond to suicide survivors will depend on a variety of individual, family, and community cultural values and beliefs. In order for a community to develop the most appropriate and effective way

of address survivor grief, community members are encouraged to discuss how they might respond as part of their suicide prevention plan development. Possible sources of support for survivors include talking with Tribal leaders, Elders, church and traditional healers, other survivors, and other community members. The extended effect of suicides among AI/AN communities adds urgency to the need for communities to determine culturally appropriate ways to reach out and support those who have

lost someone to suicide.

Survivor Groups

The Arctic Sounder, a newspaper serving Northwest Arctic and the North Slope, featured an article about a Tlingit woman originally from Hoonah who survived the death of her son to suicide. It was not long after her son died that people started telling her that she needed to “get over it. ”The woman would respond by saying, “You don’t get over it. . .You need help to get through it.” In a closing comment, she added that, “I want to let suicide survivors know that they’re not alone and they have someone to talk to.”

Many Tribal and Village communities have established survivor support groups and Talking Circles to help survivors deal with their grief. A support group facilitator’s guide written by survivor Linda Flatt is available from the Suicide Prevention Action Network (SPAN) USA. The guide is titled The Basics: Facilitating a Suicide Survivors Support Group. While a community prevention specialist and leaders, Elders, and healers may need to first review the guide to ensure that it addresses culturally relevant beliefs and ceremonies, it does make a contribution to efforts to help survivors know that they are not alone.

Preventing Suicide Contagion

Suicide contagion is a process by which exposure to the suicide or suicidal behavior of one or more individuals influences other individuals to complete or attempt suicide. This term sometimes is used interchangeably with the term “suicide clusters,” which is more specifically defined as when a group of suicides or suicide attempts occur closer together in time and space than would normally be expected in a given community.

Suicide contagion is real, and research suggests that even a single suicide within a community can increase the risk of additional suicides. Suicide contagion is not a new phenomenon, nor is it confined to AI/AN communities. Contagion has been reported within high schools, colleges, Marine troops, prisons, and religious sects, to name a few. However, teenagers and young adults

appear most at risk. This is not surprising given the characteristics of impulsiveness, difficulty with delayed gratification, and

susceptibility to peer and media pressure that are typically assigned to younger people. The addition of early experimentation with drugs and alcohol can further increase their susceptibility.

Deaths that trigger suicidal behavior, however, do not have to be as a result of a suicide. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), several clusters of suicides or suicide attempts were preceded by one or more traumatic deaths—intentional or unintentional—among the youth of the community. In one case study, two close friends of a young person who died as a result of an unintentional fall went on to complete suicide.

This research suggests a heightened potential for suicide contagion among AI/AN adolescents and young adults, given the rate of sudden deaths due to unintentional injuries. Unintentional injuries are the leading cause of death for AI/ANs ages 1 to 44. Most of these deaths are caused by traffic crashes and poisoning.

While there are no easy answers to the threat of suicide contagion, there are proactive steps that communities can take. “Postvention” is a term used to describe prevention measures that are taken after a crisis or traumatic event to reduce the risk to those who have witnessed or been affected by the tragedy. Postvention can involve both actions to help survivors through their grief process and to identify and respond to individuals who may be at risk of suicide contagion.

Identifying Individuals at Risk for Contagion

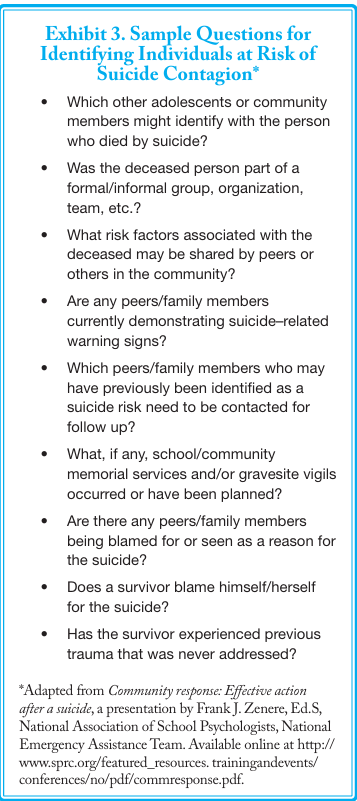

Exhibit 3 is a list of questions that community or school leaders can use to help identify individuals who may be at risk of suicide following the death of another. If someone appears to be vulnerable, a suicide conversation should follow and those at risk should be encouraged to seek help.

Developing a Postvention Plan

A community’s efforts to develop a postvention plan will be similar to its efforts to develop a broader suicide prevention plan. The community will need to understand the risk and protective factors associated with suicide contagion and develop strategies to reduce risks and enhance protective factors. Some of the risk factors, such as preexisting trauma and assuming blame for the

person’s death, are suggested in Exhibit 3.

A community should consider postvention as part of their overall suicide prevention planning rather than try to develop a response immediately after a suicide. At this time, a community may be in shock and mourning, which can prevent its members from coming together to deal effectively with the issue.

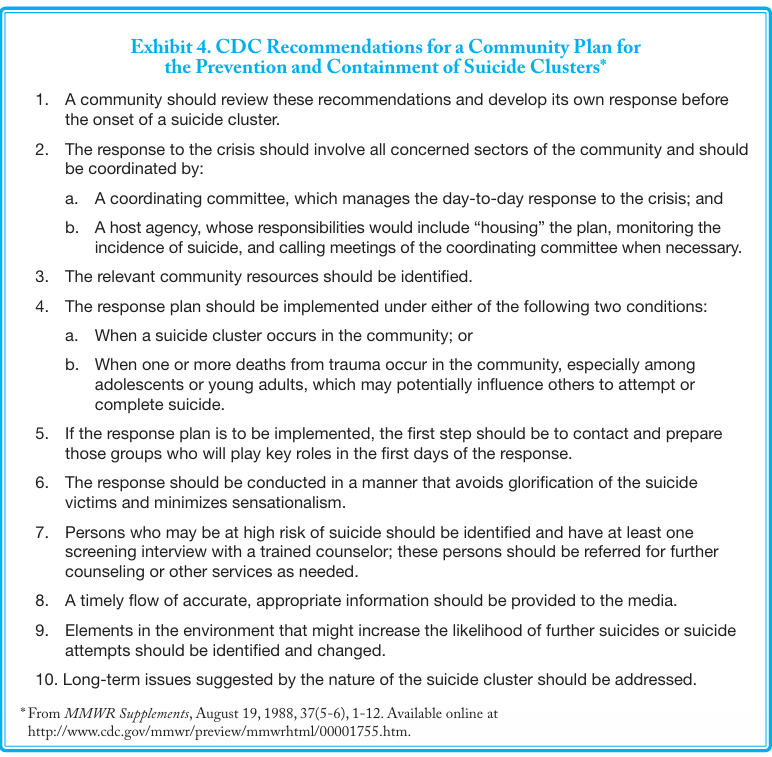

The CDC has put together a number of recommendations for postvention planning (see Exhibit 4). Each community will need to consider its particular needs and cultural strengths as it incorporates various recommendations into its own plan.

The CDC also offers general guidelines for preventing suicide contagion, which are to:

• Avoid glorifying suicides;

• Offer support to families and friends of victims;

• Identify vulnerable relatives and friends and offer counseling; and

• Enlist the support of the media.

Some of these guidelines warrant further discussion as they apply to AI/AN communities.

The first guideline is to avoid glorifying suicides. The concern is that too much “positive attention given to someone who has died (or attempted to die) by suicide can lead vulnerable individuals who desire such attention to take their own lives.” This is obviously a delicate balance without clear guidelines or rules. Many survivors become upset if told how they should grieve or what is an appropriate response. The need to avoid traumatizing suicide survivors any further is another reason to incorporate postvention planning into overall suicide prevention planning rather than as a reaction to suicide. As always, it is important to include a strong cultural foundation and to include the voices of survivors. In addition, this guideline should not be interpreted as a prohibition against the performance of Pipe or Wiping of the Tears ceremony.

Role of the Media

Another of the CDC guidelines for preventing suicide contagion is to enlist the support of the media. On the surface, this seems to contradict the recommendation to avoid glorifying suicides. Media stories can dramatize or romanticize suicides, with tragic results. For example, between 1984 and 1987, journalists in Vienna, Austria, covered the deaths of individuals who jumped in front of subway trains. The media coverage was extensive and dramatic. In 1987, an educational campaign was launched that alerted reporters to the possible negative effects of such reporting and suggested alternative strategies for coverage. Within 6 months after the campaign began, subway suicides and nonfatal attempts dropped by more than 80 percent. The total number of

suicides in Vienna declined as well.

While it is the media’s job to report on newsworthy events—whether local, Tribal, State, national, or international—it also is their responsibility to satisfy the “public’s right to know” in a way that does not exploit a community’s grief or cause further harm. The media, however, can have a powerful role in suicide prevention through responsible reporting. Stories about suicide can inform readers about the likely causes of suicide, its warning signs, trends in suicide rates, and recent treatment advances. The media also can highlight opportunities for individuals and organizations to help prevent suicide and inform community members about local resources.

The media also can be asked to participate in suicide prevention efforts before a suicide occurs. Local media can play an important and positive role in any community’s prevention plans and initiatives, especially when it comes to getting the message out about prevention events and activities. Individuals within the media make valuable partners in prevention planning efforts, and they should be recruited early in the process.

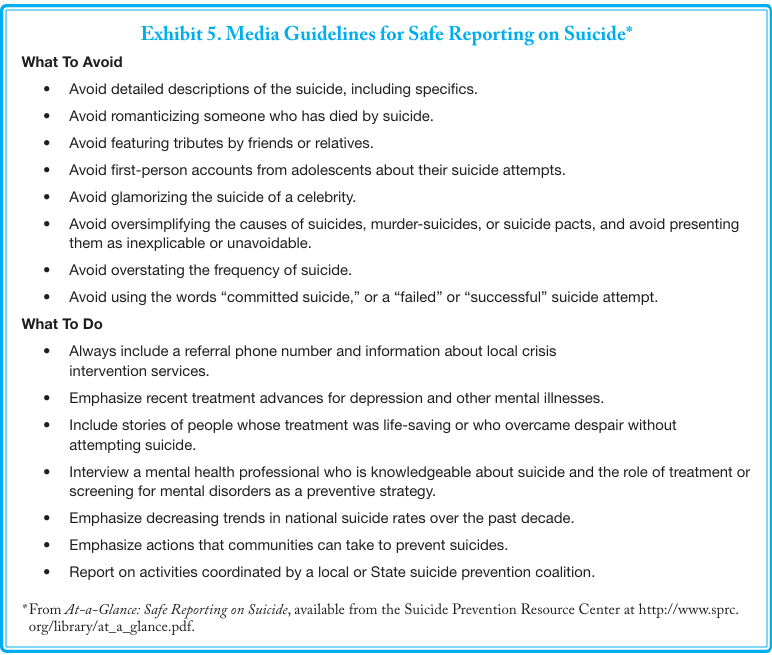

Exhibit 5 summarizes guidelines for responsible reporting that were developed in collaboration by the CDC, National Institute of Mental Health, Office of the Surgeon General, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, American Association of Suicidology, and the Annenberg Public Policy Center. At the very least, State and local media outlets should be provided with these guidelines before a community shares any detailed information about a suicide with reporters. Appendix E: Web Site Resources and Bibliography lists additional publications that provide guidance for enlisting the media in prevention efforts and for reporting on suicide.

Role of Emergency Health Care Providers

Whether in urban cities or in small towns in and around a reservation or village, the emergency department (ED) and after-hours health clinic play a unique role in health care delivery for AI/AN people in need of services. This need sometimes extends to those who have attempted suicide. The ED is their typical entry point into services and the place where many will have their first opportunity to have their suicidal behavior assessed. Such services can place a burden on a health care system already stretched. They also may be highly demanding of staff who may not be trained in suicide risk assessment and management. These statistics give some idea of the possible impact: There were 33,300 completed suicides in the United States in 2006, the latest data available at the time of this printing.96 In 2008, 1.1 million adults—0.5 percent of all adult Americans—reported having attempted suicide in the past year, according to the first national scientific survey of its size on this public health problem. About 6 in 10 of those adults received medical attention for their suicide attempt.

Attempt survivors are an extremely high risk group for suicide. Consequently, ED and after-hours clinic personnel have a critical and necessary role in suicide prevention by encouraging attempt survivors to seek help. The training of emergency health care providers should be considered in developing any community-wide prevention initiative. General guidelines for ED care is available in the SAMHSA document,After an Attempt: A Guide for Medical Providers in the Emergency Department Taking Care of Suicide Attempt Survivors. This document can be downloaded or ordered at http://www.samhsa.gov/shin. Or, please call SAMHSA’s Health Information Network at 1-877-SAMHSA-7 (1-877-726 4727) (English and Español). (An order form is included in Appendix D: Decision-making Tools and Resources and on the last page of this document.)

Role of Suicide Survivors and Suicide Attempt Survivors

Those who are most affected by suicide—including those who have attempted suicide—also have a role in preventing additional suicides. No one knows better the darkness that surrounds suicide than those who have walked in its shadow—or the light that comes from knowing that they might be able to help others avoid similar grief. The following are just a few examples of how suicide survivors are helping others to avoid the pain of a similar loss of a loved one.

Former Senator Gordon Smith of Oregon led the enactment of the Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Act in memory of his college-aged son who died by suicide. This Act provides significant funding for SAMHSA’s suicide prevention programs, and is a powerful example of how survivors have used their experiences to motivate others to action.

SPAN USA, a division of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP), is dedicated to preventing suicide through public education and awareness, community action, and Federal, State, and local grassroots advocacy. SPAN USA was born out of a family’s grief over the suicide of their daughter and the need to “transform their grief into positive action to prevent future tragedies.” SPAN USA/AFSP also demonstrates the resiliency, power, and strength of families affected by suicide.

In some communities, survivors have banded together to take turns going with the police when they inform a family of the death of a loved one by suicide so that they are available immediately to provide support.

Suicide attempt survivors increasingly are asking that they be involved in suicide prevention efforts. No one can speak with greater

understanding about outreach to and services most needed by vulnerable individuals than attempt survivors. Suicide attempt survivors also can be invaluable as mentors for those at risk. According to one participant at a SAMHSA sponsored meeting of suicide attempt survivors:

There is a lot of fear and stigma associated with attempters, and people are uncomfortable dealing with us….That

is the main reason for attempters to get involved and to get our stories out there to destigmatize the whole issue of people who

have survived attempts, and to make the point that attempters are human beings who can be productive and can help others.

IHS Emergency Response Model

The IHS has designed an emergency response model for helping AI/AN communities when tragedy strikes. Under this model, communities work through the IHS to access support from the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS). This support consists of teams of two or more USPHS mental health providers who offer emergency mental health and community outreach services. The teams work in 2-week rotations for up to 90 days of emergency response. The goal is to help the community lessen the impact of the immediate crisis and to stabilize its members so that they can begin to develop long-term solutions (i.e., planning, prevention, and implementation plans). The process for requesting and accessing such help follows.

- The AI/AN community makes a request for help to the IHS area office through the IHS service unit, Tribal health program, or urban Indian clinic.

- The IHS Area Director submits the request to IHS Headquarters (HQ) Division of Behavioral Health (DBH) director, who notifies the appropriate IHS HQ staff.

- The IHS DBH and Emergency Services (ES) staff members respond to the affected community and conduct a rapid needs assessment. While on site, HQ staff members meet with the IHS area office, Tribal health program, urban Indian clinic, IHS Chief Executive Officer, the Tribal Council, and other Tribal programs as requested.

- Depending on the rapid needs assessment and the expressed needs of the community, the IHS ES Director can forward the request for emergency assistance to the USPHS Office of Force Readiness and Deployment for action.

Conclusion

A suicide within a community—whether that community is a school, a reservation or village, or a group of individuals in an urban area who share common bonds—can have a profound impact on the lives of those who are touched by the death. These individuals need the support, comfort, and understanding of others as they work through their grief.

One danger of suicide is suicide contagion, for which suicide survivors and particularly adolescents and young adults appear at risk. Consequently, each community should strive to develop its postvention, or suicide response, plan before tragedy strikes. Such a plan is an essential part of any community’s efforts to prevent suicide by its youth and young adults. As with any suicide prevention effort, the broader the involvement of community members in helping to prevent suicide contagion, the more effective prevention will be. If suicides do occur, communities may want to request emergency support through IHS.