Chapter 5: Community Readiness

Introduction

Suicide prevention efforts often get their start as a response to a tragedy and from survivors of one or more suicides within their own family. The desire in their hearts is strong, their passions run deep, and their drive for action and results is understandable. However, as clear as the need for action may be to some, it doesn’t mean that everyone within a community agrees. Suicide prevention, by its very nature, implies changes in the status quo. And change, no matter how necessary, can be as uncomfortable and threatening to some as it is welcomed by others. Some community members may even oppose the degree of change involved, bringing community action to a halt.

Communities, just like their members, will differ in their ability to deal with all of the issues surrounding suicide and its prevention. The challenge in successful prevention planning is to understand a community’s readiness to take action and design prevention strategies accordingly. Strategies that are too ambitious are likely to fail because community members may not be ready or able to respond. Alternatively, efforts that are not ambitious enough will fail to take advantage of community commitment, resources, and momentum.

This chapter focuses on a community’s readiness for change as it relates to suicide prevention. It describes readiness as a concept, the stages of readiness, and the potential impact of historical trauma on readiness. Implications of change for American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) communities also are presented.

The “Readiness” Concept

Readiness is the degree to which a community is prepared to take action against an issue. The concept of “community readiness” evolved from research about individual readiness and the stages of change. According to this research, community readiness for change is related to the degree that its members become dissatisfied with the difference between the status quo and the desired goal or between what is happening in the present and what they value for the future. It is this discrepancy between what is and what is desired that becomes a community’s necessary motivational source for change.

Beliefs and values play a large role in a community’s awareness of such discrepancies and their dissatisfaction with them. Many of

the stories told by the Elders hold the values of what once was and the vision of what ought to be and can be for a Tribe or Village. Thus, when an AI/AN community views the behavior of its young and finds it at odds with the values of these stories, the seeds of change are germinated. When the discrepancy becomes large enough and change seems important enough, the community will begin to search for possible methods for change. The kind and degree of change possible depends on the community’s stage of readiness.

Stages of Community Readiness

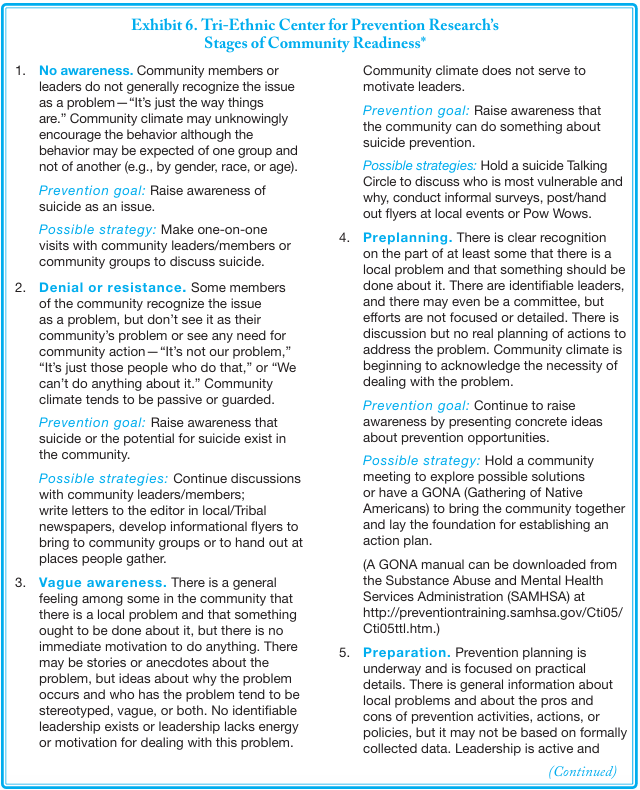

The Tri-Ethnic Center for Prevention Research conducts research into community dynamics and the social, psychological, and cultural factors that contribute to substance use, violence, suicide, and other social problems. As part of its work, the center has helped a variety of rural AI communities develop prevention plans that address these problems within their communities. Center professionals soon realized that “initiating or improving prevention programs required learning first how to change a community’s

readiness for prevention.”

The Tri-Ethnic Center has identified nine developmental stages of community readiness (see Exhibit 6). The emphasis is on following a step-by-step process to move communities through the developmental stages of change and toward the implementation of comprehensive and effective prevention programs. Each stage of readiness is accompanied by an appropriate

prevention goal and one or two examples of possible strategies.

Community vs. Community Member Readiness

Just as communities need to grow in readiness, so do their members. Not all members of a community will reach the same stage of readiness at the same time. Different community members may have different levels of motivation or be motivated by different issues. They also may demonstrate different levels of readiness to become involved at different points in time in the process.

Some members have already started and have been waiting for the rest of the community to catch up. They may see themselves as the rightful

leaders of any new program. They may believe that they should receive any grant funding coming into the community in recognition of their past efforts and involvement or so they can continue their good work. Some may still be in pain from a recent suicide and find it too difficult to talk about it, while others who have lost a loved one may feel driven to take immediate action. Others may never fully embrace community efforts.

Why someone might want to become involved in suicide prevention efforts and to what level and in what capacity will vary greatly. Regardless of their readiness stage as individuals, each person within a community may need to be honored and validated for the degree to which they feel ready to participate. The goal of prevention efforts should be to engage as many people as possible and as early as possible so that all who wish to speak can do so and all potential solutions can be considered.

Historical Trauma and Community Readiness

Eduardo Duran, director of health and wellness for the United Auburn Indian Community of Northern California, provides community interventions and consultations around the issue of historical trauma. He contends that an AI/AN community’s seeming inability to address current issues of violence, including suicide, sometimes can be traced to the internalization of the violence perpetrated on Native people for generations.

In his book, Healing the Soul Wound: Counseling with American Indians and Other Native Peoples, Duran describes how important it is for a community to engage in a healing process that reflects its own history of trauma rather than generic Native American trauma. He writes,

Preparation for community healing is critical. It is important that the community’s specific traumas be delineated first in order for the intervention to be relevant. It is useful to speak in general of the historical trauma and no one would fault the attempt at healing with this approach. However, I have found that communities, like individuals, have their own set of traumas that result in particular symptoms that need to be dealt with very specifically.

It is through this process of healing that Duran feels community members begin to release the burden of shame and guilt and to recognize the historical path that has led them to the present day. The emphasis is on the process of healing and restoring balance. Identification of historical trauma is viewed as the beginning rather than the end of a journey.

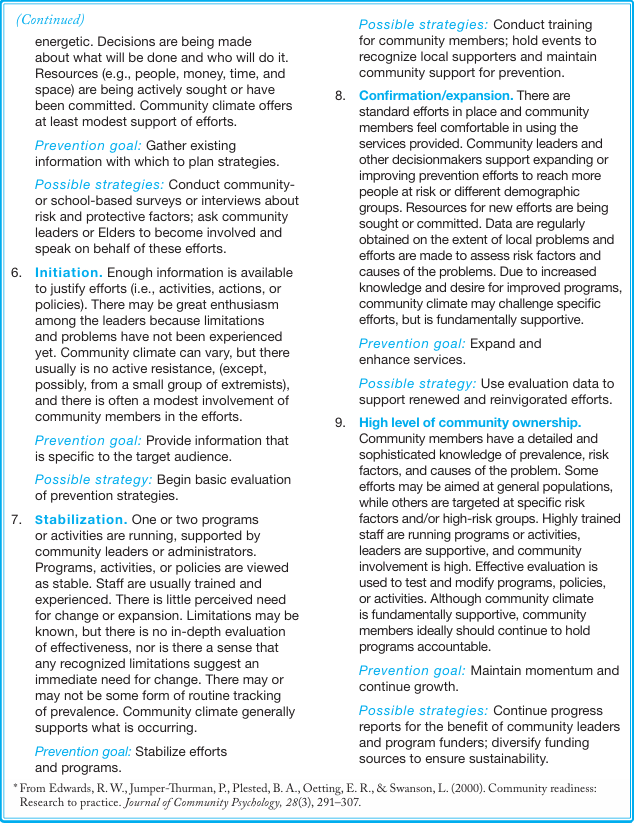

The Aboriginal Healing Foundation (AHF) has identified four phases to community healing that provide some insight into this journey. AHF is a Canadian initiative developed to address the impact of residential schools on First Nations communities. Its principle focus is on achieving community well-being by addressing personal and intergenerational trauma, which it believes

will help end cycles of abuse and violence and build strength and resiliency within the survivors and the community. As shown in Exhibit 7, the healing process moves a community from personal healing to systems transformation and from problems to solutions.

Implications of Prevention for AI/AN Communities

The preceding sections of this chapter have dealt with a community’s readiness to change and how it may prepare itself for the changes that prevention implies. This section briefly addresses some additional implications as to how change relates to suicide prevention by AI/AN communities.

Native peoples have a long history of being told that they should change. Such direction often has been unwelcome because the assumption has been that others outside of the Tribe or Village know what is best for its members.

As a consequence, a call for “change” stirs up differing emotions and reactions. Although some community members may welcome programs to reduce suicide or its risks, others may resent the implication that their current efforts are not good enough or even wrong. Even those who may be advocating for change may not agree on what changes need to happen, how soon, and who needs to be involved in the change. Talking about change and the change process early in any prevention effort, and ensuring that all voices are heard, can be essential in moving the planning process along. People are far less resistant to change when they help initiate the change.

Another potential implication of suicide prevention is that the Tribe or Village may feel under attack. Historically, AI/ANs have tended to be described in terms of weakness, pathology, and mortality rather than as being adaptive, innovative, resilient, and strong. Native people also have been romanticized, creating an equally unrealistic picture of them and their culture.

To some extent, these characterizations persist today and extend to the issue of suicide. If the suicide rate is so high in AI/AN communities, then what does that say about being a Native? Does this rate imply that just being AI/AN is an independent risk factor for suicidal behavior? Elders involved in their community’s healing process have described this negative way of thinking as a “spiritual injury, soul sickness, soul wounding, and ancestral hurt.”

Finally, there is the issue of change itself. Some Tribal and Village members might believe that the biggest challenge facing their community is the rapid changes taking place in the larger society that make it increasingly difficult for AI/AN youth to maintain their Native cultural identity. Some researchers argue that this rapid change is a primary reason for the high suicide rates in some Native communities.

Successful prevention within a community may mean a return to traditional ways or the integration of traditional ways into science-based prevention programs. As an example, mental health promotion programs work to strengthen a child’s resilience, which is the child’s ability to cope with the challenges that life can present.

The concept of resilience is not new to AI/AN people. Native youth have long been taught to stand tall and strong, to try their best, and to never give up. Combining science and tradition in one prevention program may draw upon the best of both approaches.

Conclusion

Some communities may be ready for prevention planning, while others may be ready to expand successful efforts that are underway. Still other communities may need to go through a healing process that first restores their sense of balance, worth, and empowerment before they can confront an issue as traumatic as suicide. Which prevention strategies a community is willing or able to implement will be based on its stage of readiness for change. Furthermore, the process used to develop a community’s readiness will be important in developing its long-term capacity to carry out a comprehensive and sustainable suicide prevention plan. Consensus building among all members of a community may take longer up front, but the result can be stronger, more effective prevention efforts.