Frequently Asked Questions

About underage drinking patterns

About what age do kids start drinking?

The average age at first drink is about 14, according to national surveys of 12 to 20-year-olds (Chen at al., 2011). The more we can help kids delay when they begin drinking, the better, as the younger the age of drinking onset, the greater the chance for alcohol dependence later in life (Hingson et al., 2006; Grant & Dawson, 1997).

Do boys and girls differ in drinking patterns?

Up to about 10th grade, the percentage of boys and girls who drink is about the same. By 12th grade, however, boys surpass girls, not only in terms of any use, but also in binge drinking and having been drunk in the past month (Johnston et al., 2010).

How many kids in my practice are likely to screen positive for past-year drinking?

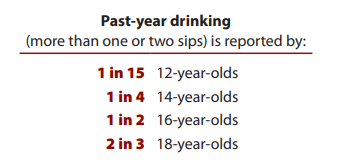

As your patients get older, you're likely to see a dramatic climb in the number who drink. Although there will be regional and local variations, national surveys show that across adolescence, we can expect a tenfold rise in any past-year drinking (the measure that correlates with this Guide's screening questions) (NIAAA, 2011):

How much do kids drink?

As kids get older, more drink and more drink heavily. In fact, you may find that dangerous binge drinking is quite common among your patients. National estimates for youth binge drinking currently use the binge definition for adult males, that is, five or more drinks per occasion. By that definition, among youth who drink, about half of those ages 12 to 15 and two-thirds of those ages 16 to 20 binge drank in the past 30 days (SAMHSA, 2010). These are likely underestimates, however, because the definition of binge drinking for most youth should be fewer drinks than for full-grown adult males (see next question).

What's a "child-sized" or "teen-sized" binge?

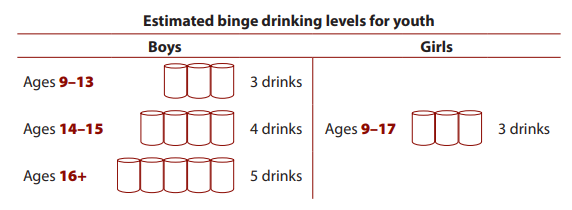

Compared with adults, children and teens are likely to have higher blood alcohol concentrations after drinking similar amounts of alcohol. Because we ethically cannot conduct clinical studies of youth drinking, we rely on mathematically derived estimates of blood alcohol levels for youth. Extrapolating from what is known about alcohol metabolism in adults, a recent study accounted for differences between adults and kids in body composition and alcohol elimination to estimate blood alcohol and binge levels for youth. The study concluded that binge drinking for youth should be defined as follows (Donovan, 2009):

(See also the FAQ on page 20 on estimating your patient's quantity of drinking.)

What kinds of alcohol are kids drinking these days?

All kinds: beer, malt liquor, liquor, wine, and "flavored alcohol beverages." Generally similar to beer in percent alcohol, flavored alcohol beverages include wine coolers and sweetened malt-based drinks that often derive their alcohol content from spirits. Although we don't yet have a comprehensive, nationwide study on youth beverage choices, a few limited studies show that distilled spirits are gaining on or overtaking beer and flavored alcohol beverages in popularity with youth and that wine is less preferred (Siegel et al., 2011; Johnston et al., 2010; CDC, 2007).

Young people are also drinking alcohol mixed with caffeine, either in premixed drinks or by adding liquor to energy drinks. With this dangerous combination, drinkers may feel somewhat less drunk than if they'd had alcohol alone, but they are just as impaired in motor coordination and visual reaction time (Ferreira et al., 2006). They are more likely to drink heavily, to be injured or taken advantage of sexually, and to ride with an intoxicated driver (O'Brien et al., 2008).

About screening

How effective are these screening questions?

The new screening questions were empirically derived through analyses of data from (1) an 8-year span (2000-2007) of nationally representative survey, which included more than 166,000 youth ages 12 to 18 (Chung et al., 2012) and (2) multiple longitudinal studies that collected information about young people as they grew up (Brown et al., 2010). While the two recommended questions have not yet been clinically tested, the analyses indicate that they are very effective predictors of adverse alcohol outcomes, both current and future. In addition, the questions are consistent with accepted standards of care in which youth are queried about friends' activities and personal health choices. (See also "What's the basis for the risk level estimates?" on page 19.)

Is alcohol screening and brief intervention effective for youth?

The evidence is clear that brief interventions are effective for adults. In fact, in 2004, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force "recommended screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce alcohol misuse by adults" (USPSTF, 2004). At that time, the evidence was inconclusive about the effectiveness of alcohol brief interventions for adolescence.

Since then, however, evidence has been accumulating on the effectiveness of brief interventions for adolescents (Jensen et al., 2011; Tripodi et al., 2010; Walton et al., 2010). In addition, in its policy statement "Alcohol Use by Youth and Adolescents: A Pediatric Concern," the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that clinicians who work with children and adolescents regularly screen for current alcohol use and use brief intervention techniques during office visits (AAP, 2010). (See also "Brief Motivational Interviewing," page 29.)

Why are we asking about past-year drinking instead of past-month drinking, when we know kids have bad memories?

All queries about past alcohol use are fallible in one way or another. Even so, responses to these queries can provide us with useful information about how children and adolescents are drinking. While data relating to past-month drinking may be more precise, data on past-year use helps to identify more youth who drink, since drinking by young people is often sporadic. When asked if they have had a drink in the past month, many youths may be able to answer "no" even though they have had alcohol at other times during the year. Additionally, research shows that responses on past-year use are predictive of alcohol-related problems (Chung et al., 2012). We ask children about their past-year use not because we know their answers are completely accurate, but because their responses can help predict symptoms and problems.

If I ask my patients how many times they drank in the past year, might this suggest to them that I expect them to drink?

You can weave this Guide’s screening questions into clinical interviews with your patients as

you see fit. If you are concerned that kids may get the message that drinking is normative if you

lead with a question about drinking frequency, then you might lead with a prescreener along

the lines of “In the past year, have you had more than a few sips of beer, wine, or any drink

containing alcohol?” For those who say yes, you can then ask, “On about how many days did you

drink?” With a prescreening question, however, you may run the risk of getting a false “no” and

bringing the screening to a stop. Use your sense of the individual patient’s likelihood of alcohol

involvement and your professional judgment to decide when to lead with a prescreener. In any

case, if you praise a “no” response, patients will get the message that you don’t find drinking at

their age acceptable.

What can I do to encourage my patients to give honest and accurate answers when I ask the screening questions?

Establishing good rapport with patients is more of an art than a science. Below are suggestions for ways to encourage accurate responses and promote productive, trusting relationships:

- Build in alone time: Build in time during the visit for parents to leave the room so you can be alone with your patient to discuss potentially sensitive issues such as alcohol.

- Explain your confidentiality policy: Make sure your patient understands that unless he or she is in danger, your conversation will remain between the two of you. You can discuss your confidentiality policy with parents and children together - both need to be familiar with it.

- Be on their side: Explain to your patients that you are not singling them out, but that you talk to all of your adolescent patients about alcohol use and other health risks. Your purpose is to keep all of your patients healthy and to offer good medical advice - not to get anyone in trouble.

How do I prioritize screening for alcohol in relation to other risk behaviors such as unprotected sex, smoking, and use of other drugs?

Alcohol use is an excellent place to start screening for risky health behaviors for two main

reasons. First, talking with your patients about alcohol has the potential to save lives. Drinking is

associated with three top causes of death among adolescents, the first being unintentional injury,

usually by car crashes, followed by homicide and suicide (CDC, 2008).

Second, starting with questions about drinking can help you determine whether asking questions

about other risk behaviors is a high priority. Alcohol is the drug used by the greatest number of

adolescents (Johnston et al., 2010), and for many young people it is also the first substance they

try. Youth who don’t use alcohol are unlikely to use any other substances, whereas youth who are

heavily involved with alcohol are at increased risk for using other substances and for other risktaking behaviors (NIAAA, 2011; Biglan et al., 2004).

Why should I bother screening kids that I'm almost positive aren't drinking alcohol?

Talking about alcohol—with all of your patients—shows them that you care about their health

and are concerned about the risks. You may be surprised to discover how widespread alcohol

use really is among adolescents. Despite your best instincts, you will find that even “good kids”

drink—and that their alcohol use can cause problems. Discussing alcohol with every adolescent

who walks through your door helps make sure no one falls through the cracks.

For kids who are not drinking, this conversation offers you the opportunity to praise and

encourage the smart and healthy choices they are making. We know that positive reinforcement

works and this is a great opportunity to use it. In addition, research indicates that youth hold more

positive perceptions of health care providers who bring up sensitive topics such as substance use,

suggesting that young people may expect this standard of care (Brown & Wissow, 2009).

About guiding patients who do not drink and their parents

For younger patients who have not started to drink, what anticipatory guidance should I provide to patients and parents?

For patients who are not drinking: Be sure to praise them for making the decision not to

drink. Recommend that they get involved in activities that build on their strengths, choose friends

who also make good choices, and avoid situations where alcohol or other drugs are

easily available.

For their parents: Parents may wonder if allowing their children to drink with them in the

home will help protect them from alcohol problems later in life. You can let them know that

most studies indicate that the opposite is the case (McMorris et al., 2011; NIAAA, 2010) and

that a permissive home environment can increase the odds for teen alcohol problems. Research

suggests that parents who don’t want their kids to drink do have an important influence over

their kids’ alcohol decisions, even through high school and the transition to college (Abar et al.,

2009; Walls et al., 2009; Wood et al., 2004). Suggest that parents set clear expectations, such as

making a house rule of no underage drinking, with equally clear and consistent consequences.

Offer resources for learning about underage drinking (see page 38), and encourage parents to

discuss the realities and consequences with their kids. Remind them that they can find many

“teachable moments” about alcohol risks in the news and entertainment media. (See page 22 for

handling a situation in which parents themselves have alcohol problems.)

What parent educational materials or parenting Web sites can I suggest to families?

See Additional Resources at the end of this Guide on page 38.

About risk assessment

What's the basis for the risk level estimates?

The risk level estimates in this Guide—and the screening question on drinking frequency—come

from analyses of national survey data on alcohol use by more than 166,000 youth ages 12 to 18

(Chung et al., 2012). Researchers looked for connections between drinking pattern variables and

concurrent symptoms of an alcohol use disorder (AUD), whether alcohol abuse or dependence, as

defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, published

by the American Psychiatric Association.

Consistently, they found that the number of drinking days in the past year predicted the presence

of AUD symptoms more accurately than the quantity of alcohol consumed or the frequency of

binge drinking. It’s important to note your patients do not need to be completely accurate when

estimating past-year drinking, because the reported frequency predicts the presence of AUD

symptoms.

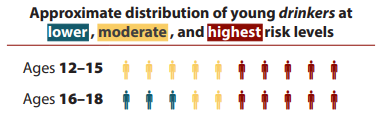

Among my patients who drink, what proportion will be in the "lower," "moderate," and "highest" risk categories?

National data provide the big picture, which will vary somewhat by region. At ages 12 to 15 years,

any drinking is considered at least “moderate” risk, and half of drinkers in this age group drink

frequently enough to be in the “highest risk” category. At ages 16 to 18, about one-third of

drinkers are at “lower risk,” one-fifth at “moderate risk,” and just under half are at “highest” risk

(NIAAA, 2011).

How can I remember the cut points for the different risk levels?

When you’re getting started, you can use the Pocket Guide (enclosed), which contains the risk

estimator chart. Over time, you will get a feel for the risk cut points for the different ages and the

correlated intervention levels. To facilitate that process, you might focus first on the “highest risk”

cut points, which identify the kids who need the most attention and possibly a referral.

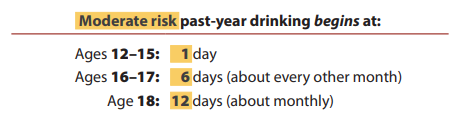

Once those become familiar, you can round out the picture with the cut points for “moderate risk”:

Again, these risk levels and cut points are not absolutes, but instead indicators to help you gauge

the extent of your professional response.

As part of the risk assessment, how can my patient and I estimate drink quantities?

That can be a challenge. Some youth drinking choices are easier to quantify (shots, cans, bottles,

and beer from a keg served in 16-ounce plastic cups), whereas others are inventive, built for speed,

and harder to measure (such as gelatin shots and beer chugged from funnels called beer bongs).

Fortunately, with this Guide, you don’t need precise quantity estimates to gauge your patient’s

risk because the number of drinking days in the past year is a powerful predictor of risk on

its own. Still, for moderate and highest risk drinkers, you will want to ask about quantity of

drinking to round out your risk assessment.

For some perspective, the tables below provide information about “standard drink” sizes

and the approximate number of standard drinks in common containers for beverages

with different amounts of alcohol by volume (or alc/vol). (For more information, visit

www.RethinkingDrinking.niaaa.nih.gov.)

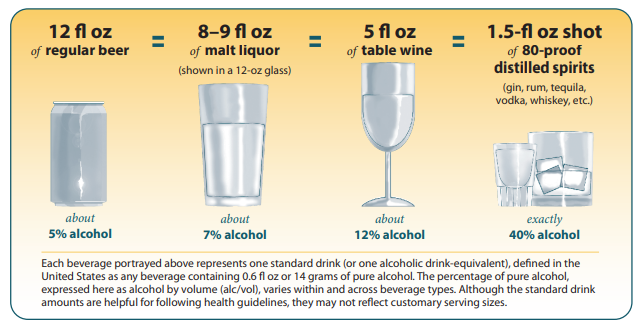

What counts as a drink?

In the United States, a standard drink is any drink that contains about 0.6 fluid ounce or 14 grams

of pure alcohol. Although the drinks below are different sizes, each contains approximately the

same amount of alcohol and counts as a single standard drink.

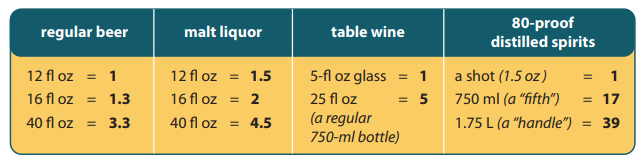

How many drinks are in common containers?

Below is the approximate number of standard drinks in different-sized containers of:

These examples are a starting point for comparison. Alcohol content can vary greatly across

different types of beer, malt liquor, and wine. “Flavored alcohol beverages” or “alcopops” have

a particularly wide range, from about 5 percent to 12 percent alc/vol. For other beverages, the

differences may be smaller than you might expect. The most popular light beers, for example,

have almost as much alcohol as regular beer.

What do you mean by "incorporate what else I know" about my patient and his or her family in my risk assessment and intervention?

Your awareness of family factors such as these would heighten concern about the degree of risk;

- A history of alcohol problems in parents or siblings

- Divorce or other challenging transition

- Low parental involvement in kids' lives

- Kids who have to much unsupervised time or say they're "bored"

In addition, details you may already know about your patient's strengths, interests, and health conditions can help personalize and strengthen your intervention messages. For example:

- Athletes or scholars who drink could compromise their performance in sports or academics and, in school with zero tolerance policies, be kicked off teams or clubs if caught drinking even once.

- Kids with chronic conditions such as diabetes, anxiety, or depression can complicate management of their conditions by drinking.

What are "acute danger signs" - behaviors so potentially dangerous that they require a "highest risk" intervention on the spot?

The most common and potentially lethal danger sign is drinking and driving. Unless a patient

who drinks and drives commits to stopping, an immediate intervention is warranted. This can

include informing the patient’s parents, recommending that they take away car keys and driving

privileges, and referring the patient for treatment.

Besides drinking and driving, other signs of acute danger that indicate a “highest risk”

intervention and probable referral include:

- High, potentially lethal volume intake

- Combining alcohol with other drugs, especially sedatives

- Substance-related hospital visits or injuries; alcohol poisoning

- Unplanned or unprotected sexual activity associated with alcohol use

- Signs of alcohol addiction; drinking daily or near-daily; having memory blackouts

- Use of intravenous drugs

About Intervention

See also the summary of "Brief Motivational Interviewing" on page 29.

What should I do if my patient says, "I'm not going to stop"?

There are several ways you can choose to handle a negative response.

For kids who seem at relatively lower risk, you can ask permission to give brief advice, provide

the advice if accepted, and ask what they make of it. For example, you might say: “You ultimately

make the decision, but at the same time, I recommend that you don’t drink alcohol at all. You are

a good [student, athlete, sibling, friend]; I would hate to see alcohol get in the way of your future

and the things you care about. What do you think?” For those who decline the advice, suggest

that they think about your conversation a bit more.

For kids who are at moderate or highest risk, motivational interviewing should be helpful. For

example, you might say: “I understand you recently had a blackout from drinking too much

and your parents were very upset. You agree that you drank too much that night, and that was

dangerous and a little scary. How do you want to move forward?” Consider setting up a followup

appointment, as just one additional session of motivational interviewing can make a difference. In

some cases, you may need to break confidentiality and inform the patient’s parents. In others, you

might suggest a referral to a counselor.

What, if anything, should I do differently if I know that one or both of my patient's parents have alcohol-related problems?

Though a minority, the youth in your practice whose parents have an alcohol use disorder are

among those at the greatest risk. How you decide to approach this issue will depend on your

assessment of the extent of the parental problems. If you sense that one parent would be an ally,

then referring that parent to an expert for help in dealing with family drinking problems would be

appropriate and advisable.

If, however, both parents appear to be heavy drinkers or dependent on alcohol, your concern may

be better expressed generically. As an example: “Justin is at an age when all parents need to be

concerned about their children’s alcohol use. Kids this age often do not even know when they are

in a dangerous situation. Of course, how much their friends drink is usually a big influence. But

many people aren’t aware that the amount of drinking by family members and the easy availability

of alcohol in the home may make it more difficult for their child to know how to manage when risky

drinking situations occur. For this reason, I ask that families be open to the possibility that expert

advice may be useful in keeping their children safe. We have some good resources available. May I

make that connection for you? What are your thoughts about a referral?”

In these circumstances, even if the offer of help is refused, it is important for health care providers

to make a point at each visit of expressing concern, with a focus on both the risk-taking behaviors

and the specific vulnerabilities of the child’s developmental stage.

Should I recommend any particular specialty treatment for patients who need referrals?

One size doesn’t fit all when it comes to alcohol treatment options. Fortunately, a range of

effective treatment choices is available. A recent meta-analysis found that several types of

substance abuse treatment can reduce adolescent alcohol abuse (Tripodi, 2010), including

individual-only and family-based interventions. In contrast to earlier meta-analyses, this study

generally found larger effect sizes in individual over family-based interventions. Either can

be effective, however, so the authors caution against unequivocally recommending individual

therapy over family-based at this point.

Of note, the analysis found that three of the therapies with large effect sizes included brief

interventions. Among the longer-term treatments with larger effect sizes were cognitivebehavioral therapy integrated with a 12-step approach, cognitive-behavioral therapy with

aftercare, and multidimensional family therapy. Also found effective, with medium effect sizes,

were integrated family and cognitive behavioral therapy, behavioral treatment, and triple modality

social learning.

For suggestions on how to find adolescent substance abuse specialists and programs in your area, see

Referral Resources, page 34. It is a good idea to develop working relationships with local resources

and practitioners, so you can make solid, confident recommendations and provide a continuity of care.

How can I help a patient who struggles to remain abstinent or who relapses?

Changing drinking behavior is a challenge, especially for patients who are alcohol dependent.

Although you will have referred alcohol-dependent patients to specialty treatment, of course you

will still see them for other visits. If you learn that a patient has relapsed, recognize that he or she

may have developed a chronic disorder that requires continuing care, just like asthma or diabetes.

The most important principle is to stay engaged with the patient and to maintain optimism about

eventual improvement. In addition:

- If the patient objected to the initial referral, seek another appropriate, acceptable option.

- Assess and address possible triggers for struggle or relapse, including stressful events, interpersonal conflict, insomnia, chronic pain, or high-temptation situations.

- Address depression, anxiety disorders, or conduct problems, referring to specialty treatment if needed.

- Point out any progress while noting the difficulty and multi-step nature of making a change (see also step 4, page 12).

Depending on the family situation, you might also encourage family members to participate

in mutual support groups such as Al-Anon. Continue to collaborate with the family and any

treatment providers as the recovery process continues.

About office procedures

How can a clinic- or office-based screening system be implemented?

One option is to allow patients to fill out a pen-and-pencil or computer-based questionnaire either

in the waiting room or prior to the visit, as long as they have privacy to do so. Another is for

the health care provider, preferably one who knows the patient well, to ask the questions during

office visits. A third is for other clinical personnel to screen patients during check-in. If a clinical

assistant will screen patients instead of the primary health care provider, be sure to work out

record-keeping to facilitate followup in the exam room.

For further guidance, see the American Academy of Pediatrics’ new manual on implementing

mental health screenings called Addressing Mental Health Concerns in Primary Care: A Clinician’s

Toolkit. Included in the Toolkit is a readiness to screen checklist and suggestions on how to prepare

the office staff. You can access these materials at https://services.aap.org/en/patient-care/mentalhealth-initiatives/.

Can I be reimbursed for conducting alcohol screening and brief intervention?

Progress has been made in recent years, such that with proper coding it’s now possible to be

reimbursed for alcohol screening and brief intervention. See the latest AAP publication Coding

for Pediatrics for up-to-date, detailed information (AAP, 2020). Two caveats: Check with your

patients’ insurers, as some companies reimburse only mental health care providers for substance

use diagnoses. In addition, if you are treating a patient without the parent’s knowledge, be aware

that confidentiality will be compromised if diagnostic codes are included in explanations of

benefits sent to a parent.